How institutions flourish or fail

A provisional framework for institutional flourishing

Note: This is a first draft of a piece that was published in Comment Magazine. You can read the final (and improved!) version here.

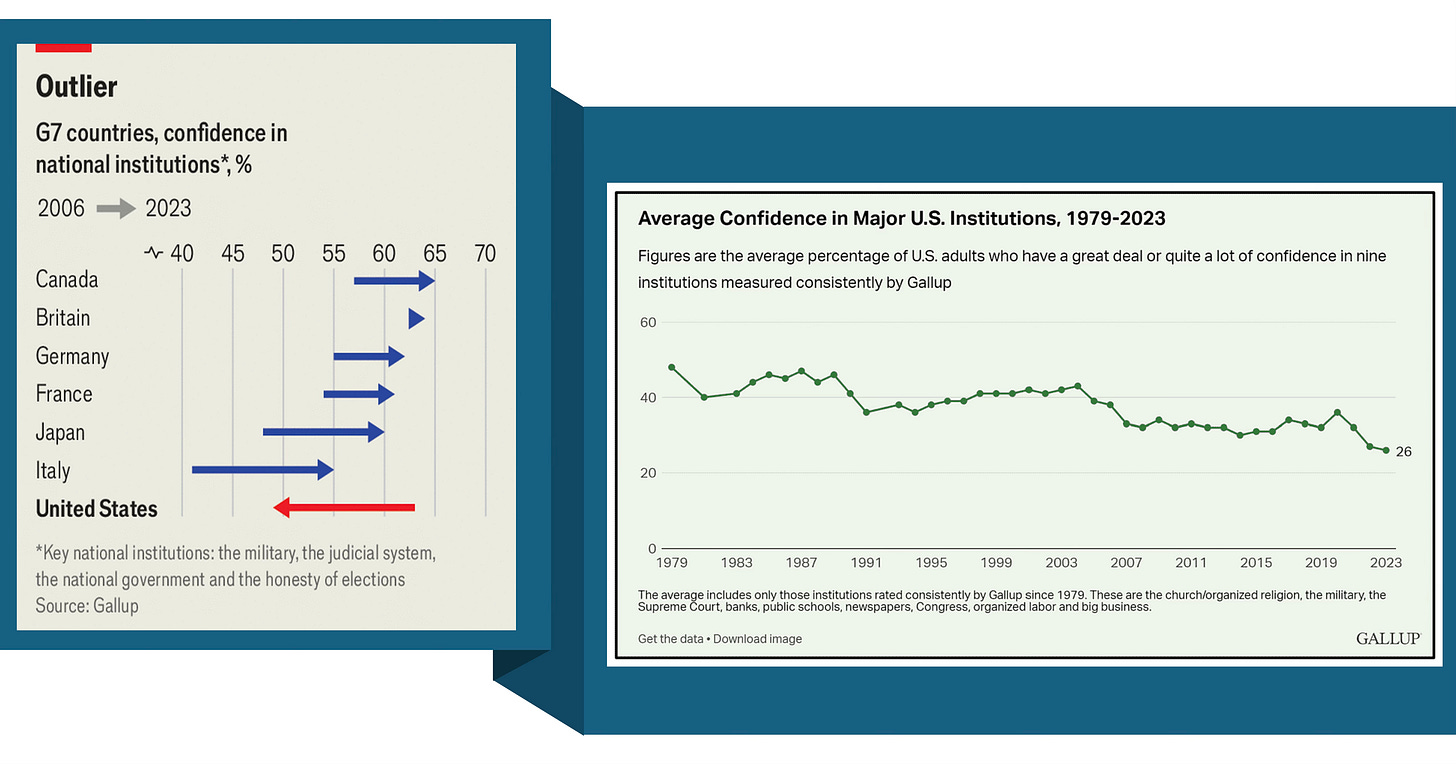

If you stand on any street‑corner in America and ask strangers whether they trust Congress or big business or news media or the church, most would dodge you like you were a foul-smelling obstacle—but among those who do stop to hear your question, at least seven out of ten would say no.

Gallup’s 46‑year trend shows average public confidence in bedrock institutions has collapsed from nearly 50 percent in 1979 to just 26 percent today. This isn’t unique to America. Across the OECD, fewer than four in ten citizens now say they have “high or moderately high” trust in their national governments.

Institutional decay fuels social fragmentation and threatens the viability of our societies. But what does it mean for an institution to flourish? And why are so many of them failing?

Institutions, as sociologist W. Richard Scott defines them, “are multifaceted, durable social structures, made up of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources.” Or as Yuval Levin more succinctly puts it, they are the “durable forms of our common life.”

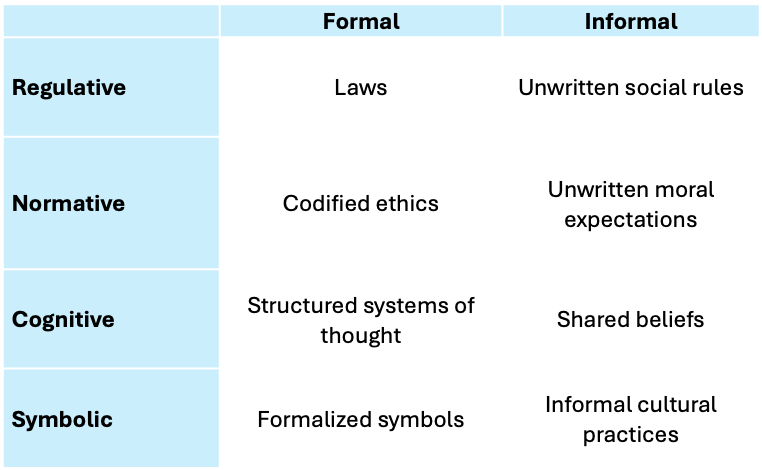

Institutions can be analyzed at different levels. At the micro-level, they consist of rules, norms, and symbols that may be formal (e.g., laws or policies) or informal (e.g., unwritten customs. A handshake is an institution in this sense).

At the meso-level, we find complex institutions such as a family, a school, or a parish, which are single organizations or communities where those rules and norms are bundled into concrete roles, practices, and rituals. And at the macro-level, these entities form institutional complexes like education, religion, or government, which are ecologies of many institutions interacting together.

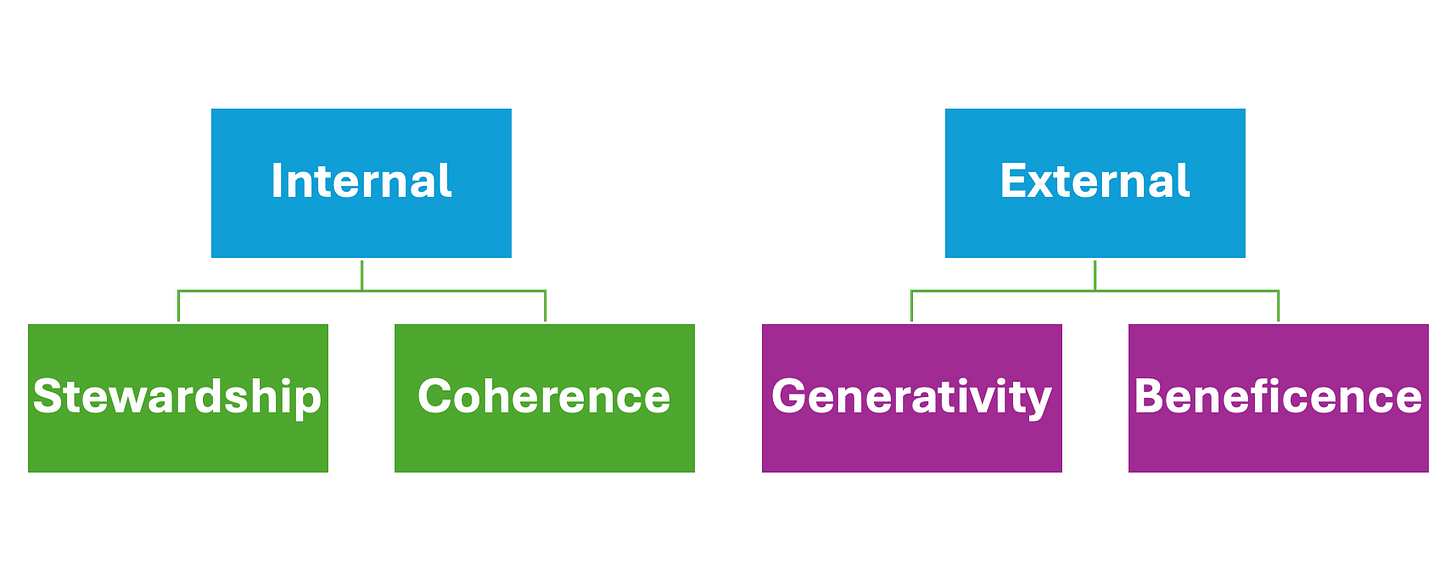

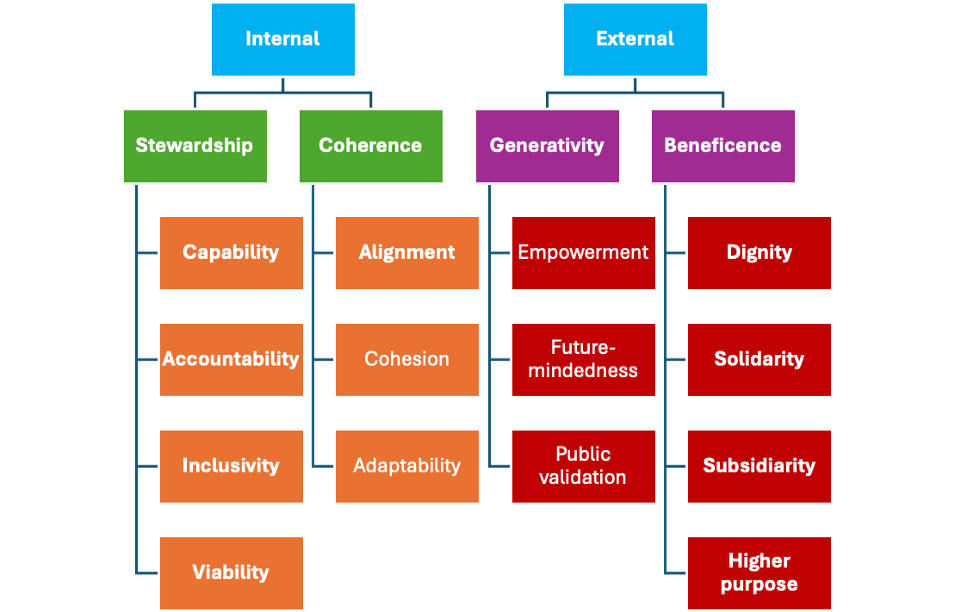

I founded the Institutional Flourishing Lab at The Catholic University of America to better understand the factors that shape the flourishing of institutions such as business, science, and religion. This is an attempt to weave a thread across my various research projects. From my research, I can identify four criteria for the flourishing of meso- and macro-level institutions, two internal and two external, each of which has several components.

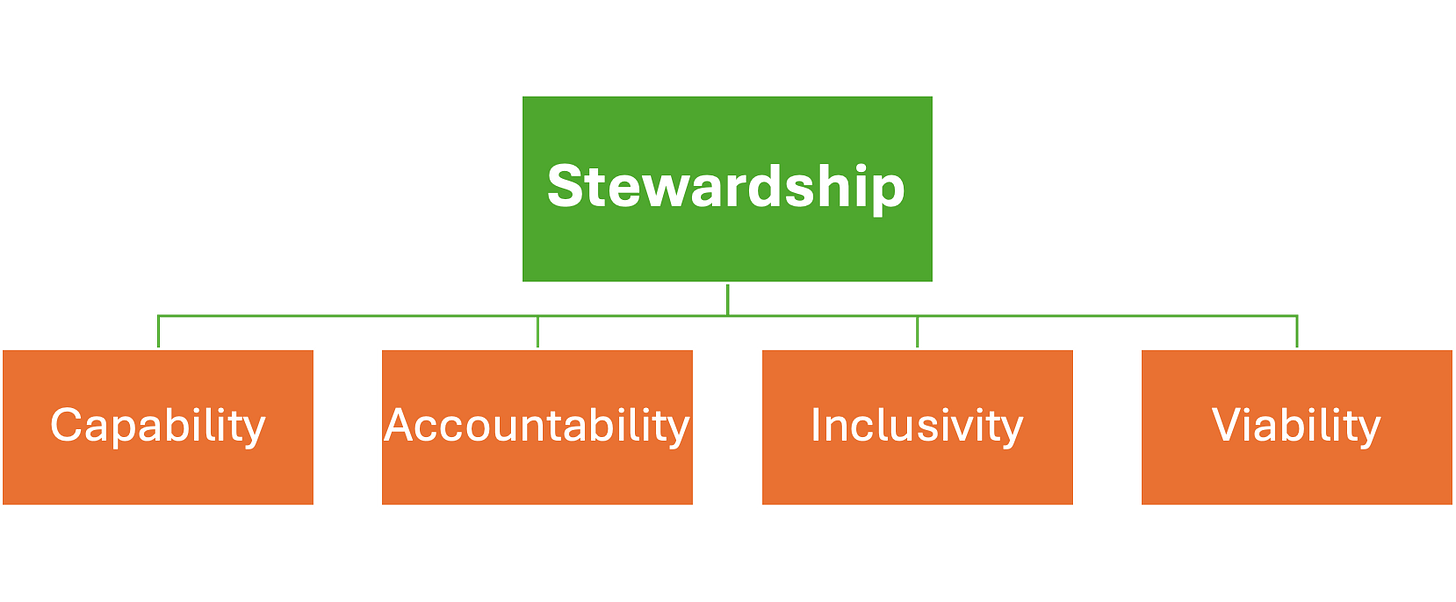

(1) Stewardship

If institutions are the durable forms of our common life, they need to skillfully and faithfully manage—and care for—what’s been entrusted to them. This sort of stewardship has four components.

(a) Capability: Technical and moral competence to fulfill core promises. E.g. the Catholic Church’s mishandling of clergy abuse and corporate scandals like Enron reveal catastrophic failures of institutional competence, where governance, fiduciary responsibility, and the safeguarding of the vulnerable all collapsed.

(b) Accountability: Mechanisms to hold leaders and members answerable to standards of their role. As Yuval Levin argues, institutions form us and should constrain members to act in accord with their institutional roles. Today, however, many institutions have become performative rather than formative, as members use institutions as platforms for personal gain (e.g., politicians chasing media followings rather than serving the common good).

(c) Inclusivity: Demonstrated care for all stakeholders in the institution, especially the marginalized. E.g., Minority groups can distrust science and medicine because they lack representation in those fields and don’t experience these institutions as attentive to their needs or concerns.

(d) Viability: Basic material and demographic stability required for long-term flourishing. Basic structural health (e.g., balanced budgets, sustainable membership, and good governance) is needed to secure continuity across generations.

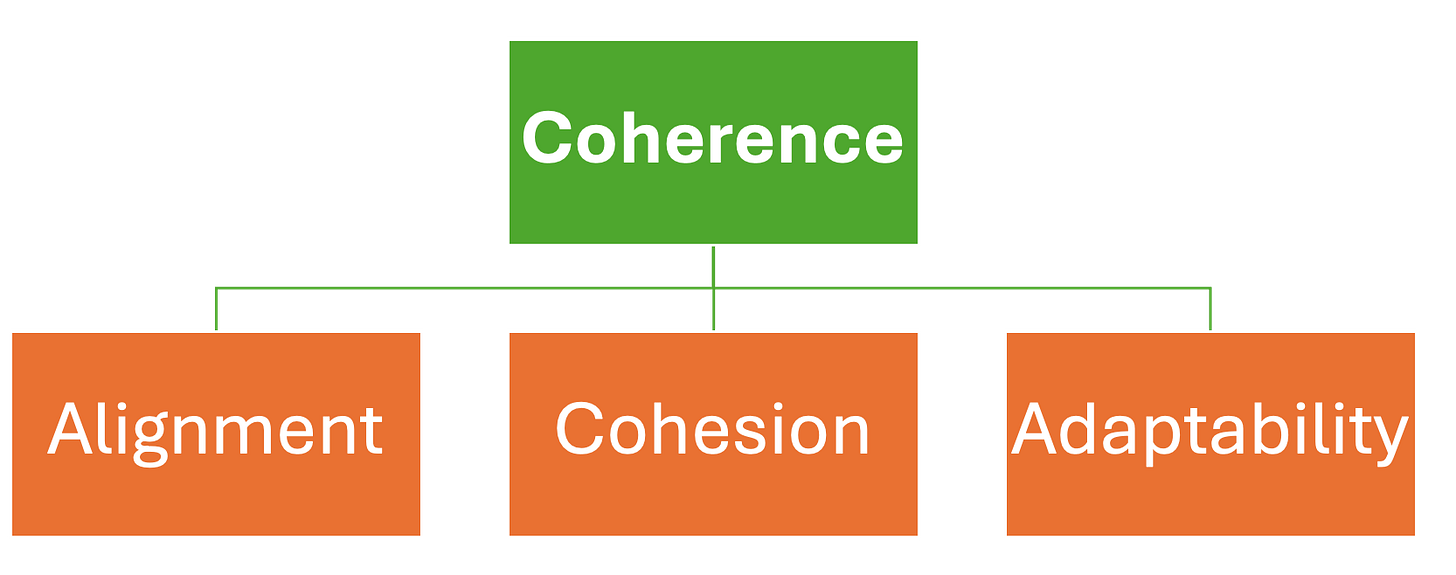

2) Coherence

For institutions to flourish, their internal elements need to hang together. This has three aspects.

(a) Alignment: Values, roles, and incentives must point in the same direction.

i. Value alignment means institution members share what matters. In the National Study of Catholic Priests, we found that most Catholic bishops claimed they would help priests who approached them, but very few priests thought their bishop would—showing a gap in perceived values.

ii. Role alignment means responsibilities match calling. Scientists buried in bureaucratic work and grant writing suffer role strain when roles drift from their primary tasks.

iii. Incentive alignment means rewards reinforce mission. Policies like corporate stack ranking tell employees to collaborate but evaluate them on a competitive basis, effectively undermining coherence and turning them into mercenaries.

(b) Cohesion: Scripts, models, and habits bind members to a shared mission.

i. Scripts: The stories people tell each other shape expectations. In corporations and medical schools, a “hidden curriculum” often develops that contradicts the formally espoused mission.

ii. Models: In any institutional context, we inadvertently imitate those who seem to be thriving. In competitive workplaces, however, mimetic rivalry and scapegoating spread when the wrong models are elevated.

iii. Habits: Daily routines form dispositions. Institutions that ritualize cutting corners cultivate vice, while those that honor craft and patience build virtue.

(c) Adaptability: The ability to learn, experiment, and adjust. Institutions that flourish are not rigid. They can innovate while remaining true to their core mission and function. Without this flexibility, institutions become brittle, like Kodak in the digital era: aligned internally, but unable to successfully adapt to external change.

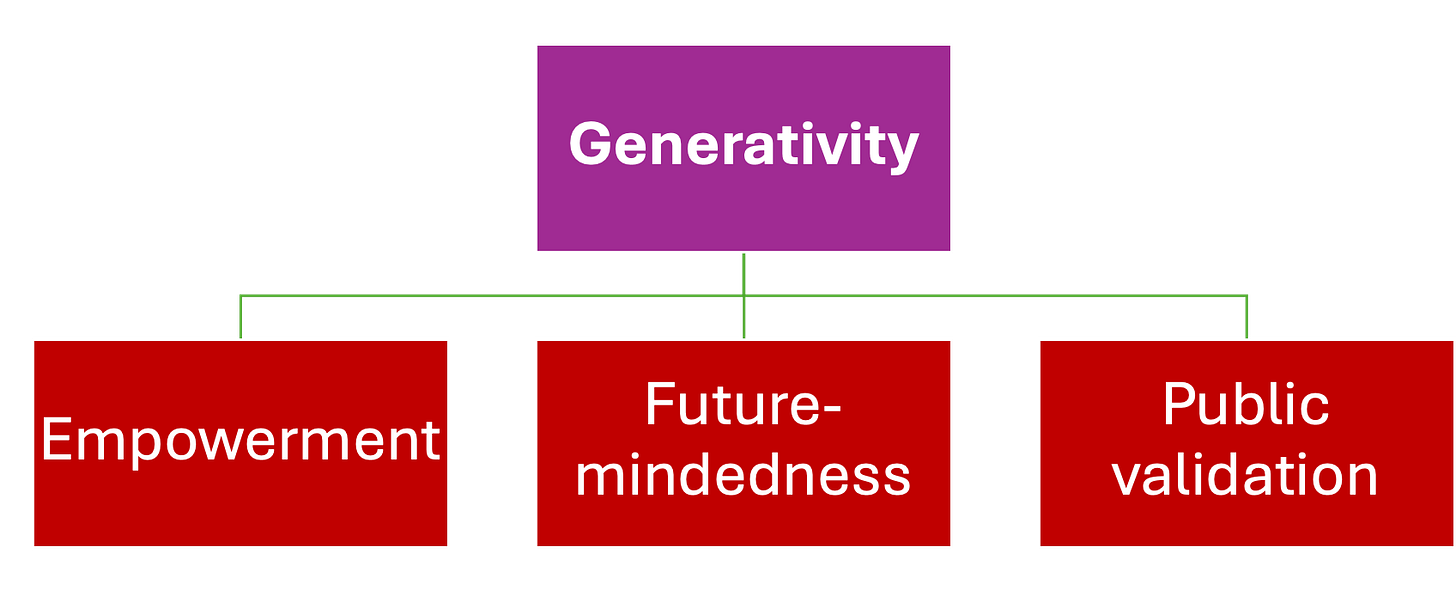

3) Generativity

In psychology, generativity refers to the capacity to care for and guide future generations. What sociologist Mauro Magatti calls social generativity similarly names the ways institutions generate long-term benefits that extend beyond their boundaries.

This entails three main principles:

(a) Empowerment: Using institutional power to strengthen others rather than dominate. E.g., Loccioni Group in Italy encourages employee spin-offs instead of binding talent with non-compete clauses, thus bolstering innovation across its sector. Scientists who mentor students well and celebrate launching them into new careers empower knowledge to spread.

(b) Future-mindedness: Innovating with long horizons while rooted in tradition. E.g., Brunello Cucinelli runs his company on a declared 200-year horizon, restoring the public spaces of the village of Solomeo, where the company is based, while investing 20% of company profits into the local community and the education of artisans.

(c) Public validation: Gaining recognition or imitation that inspires others to act. Mondragon’s cooperative ethos in Spain has encouraged worker-ownership experiments worldwide, and Aravind Eye Care’s radical affordability has motivated new approaches to accessible healthcare.

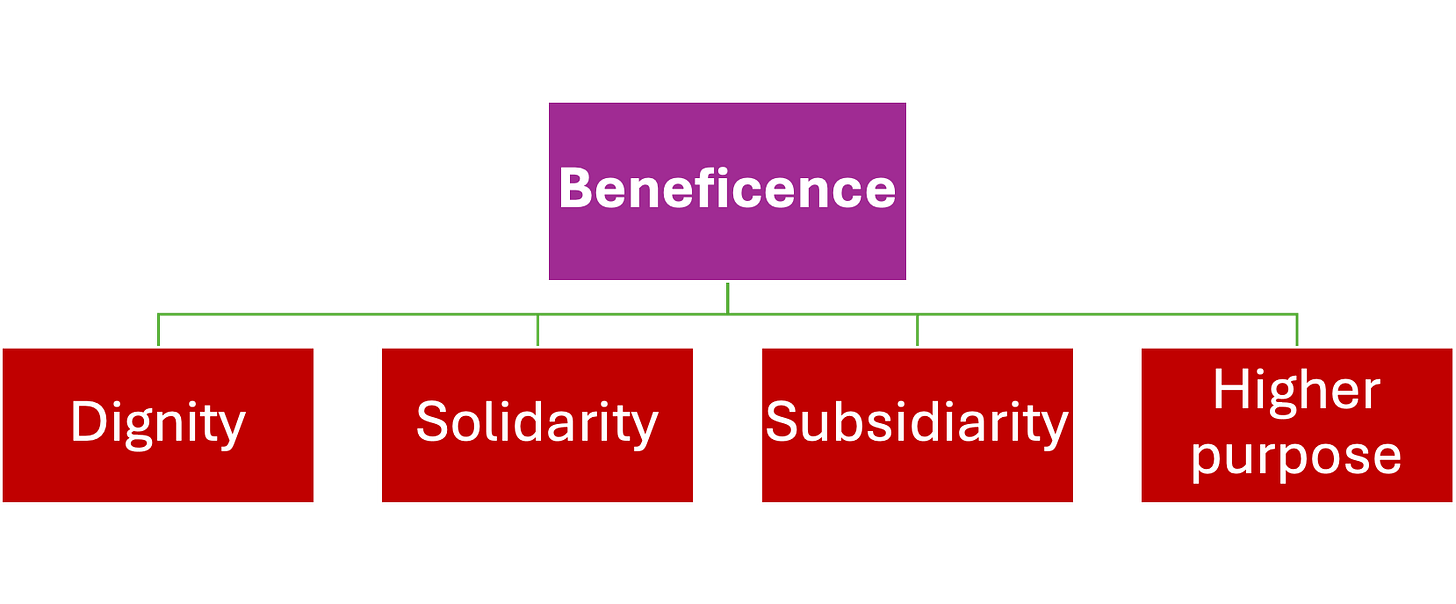

4) Beneficence

Flourishing institutions need to be ordered towards the common good and to higher purposes than their own survival. (Beneficence may not be the ideal word for this, but it’s the best I can come up with for now).

This entails four principles that I have derive primarily from a body of work known as Catholic Social Teaching:

(a) Dignity: Treating every person as an end, not a means. E.g., paying employees fairly for the time excellence requires, even if it may reduce profit margins.

(b) Solidarity: Acting out of recognition of our shared humanity, especially in defense of the vulnerable. E.g., faith communities that mobilize funds to support struggling families in their neighborhood, regardless of membership.

(c) Subsidiarity: Locating decisions as close as possible to those directly affected. E.g., governments and firms that empower local ownership and responsiveness rather than centralizing control.

(d) Higher-order purpose: Orientation to transcendent horizons beyond self-interest. E.g., scientists who see their research as part of humanity's ongoing search for truth rather than for boosting prestige.

These internal and external criteria for institutional flourishing apply most obviously to institutions such as firms, schools, and governments. But they also point to what it means for other institutions such as families to flourish, though in softer and more relational registers: e.g., competence includes care, accountability implies mutual responsibility, and viability becomes intergenerational sustainability.

There are also more domain-specific factors. For instance, not all factors that contribute to the flourishing of a family are going to matter for the flourishing of a market or government, and vice-versa. But what I have tried to identify here are general criteria that are broadly applicable across domains that I’ve seen recurring in my research.

This model is a work in progress and I’d welcome your suggestions for its improvement and further development.

This is a really interesting typology. I've been interested in institutional theory especially within organization studies for some time. Some of my current work in progress attempts to explain institutional stability in terms of individual flourishing. Two questions about this typology come to mind: 1. What does it explain? Can we use this to understand, for example, why individuals seek to change institutions or work to maintain it, or why institutions stabilize? 2. How do different levels of analysis figure into this typology? We could imagine a scenario where flourishing institutions conflict with interests of participants or others affected by them. Similarly, could a flourishing firm or government be in tension with a flourishing family or university? Likewise, individuals are impacted by multiple institutions how does this sustain or obstruct the motivations needed to sustain such institutions? Finally, what assumptions are needed about the individuals affected by these institutions? Could we extend it by incorporating an account of individual flourishing?