Is Science a Vocation?

Most scientists think so. But what do they mean by it?

We have long regarded certain professions as higher callings or vocations: nursing, teaching, and especially clergy and religious life. The concept of vocation, after all, has religious origins, rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition, where it signifies a divine summons to serve.

What about science? Is science more than just an occupation?

The German sociologist Max Weber, more than a hundred years ago, suggested as much in a famous lecture titled “Science as a Vocation.” But he saw it as a peculiarly difficult sort of calling: science demanded the ascetic devotion, personal passion, rigorous commitment, and unrelenting discipline of religion—but without offering the metaphysical or spiritual assurances traditionally associated with a religious calling. Science, for Weber, was an engine of the disenchantment of the world, stripping away the magic and mystery from reality. Scientists, he argued, had to pursue a calling in which they knew they contribute to a rationalized, fragmented understanding of reality rather than ultimate truth.

Today, more than a hundred years after Weber’s famous lecture, how do things stand? Institutionally, science has become significantly more bureaucratized, specialized, and precarious as a career. How do scientists make sense of their work existentially in such conditions?

Do scientists see science as a vocation?

In 2021, my team and I surveyed more than 3000 physicists and biologists across the US, UK, Italy, and India, and found that most scientists see their work as a vocation.

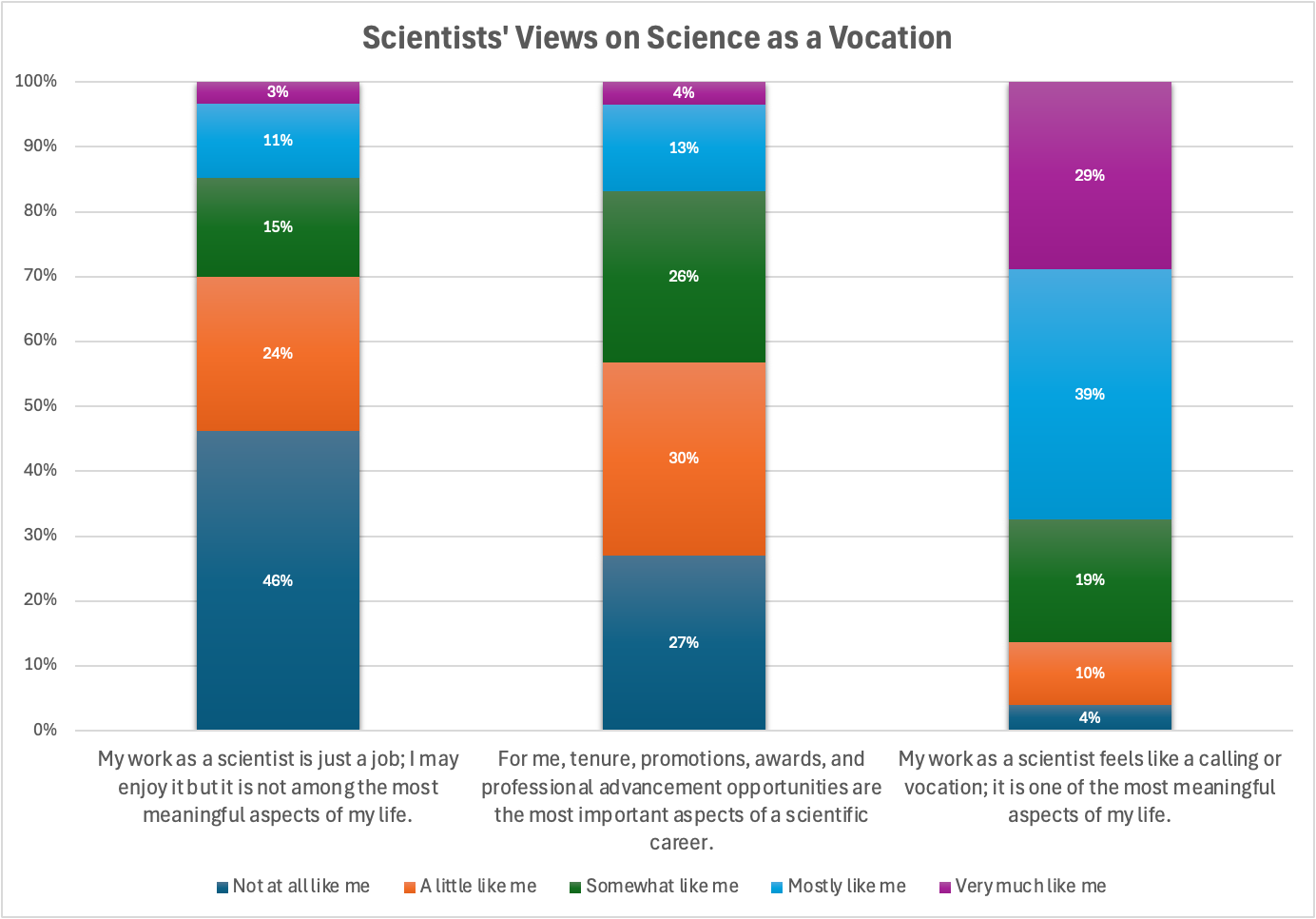

On our survey, we adapted a question from the work of Yale management scholar Amy Wrzesniewski, who developed a typology of work as a job, career, or calling. We asked scientists to what extent each of the following statements reflected their views about science:

1. My work as a scientist is just a job; I may enjoy it but it is not among the most meaningful aspects of my life.

2. For me, tenure, promotions, awards, and professional advancement opportunities are the most important aspects of a scientific career.

3. My work as a scientist feels like a calling or vocation; it is one of the most meaningful aspects of my life.

We found that nearly seven in ten scientists (68%) identified strongly or somewhat with viewing their work as a vocation, describing it as one of the most meaningful aspects of their lives, while only a small minority (14%) strongly identified with viewing science merely as a job.

Following the survey, we interviewed more than 300 of these scientists between 2021-2024 to understand how they find meaning in their work. We found that they articulate their sense of vocation in three distinct but overlapping ways: expressive, civic, and transcendent.

Expressive calling: Science as identity and passion

Scientists with expressive callings see their work as deeply intertwined with their personal identity. As one US biologist put it, “I'm a scientist; it's who I am. It is in the fabric of who I am.” Similarly, an Indian physicist described his science as “dictated from my inner self, not from any external anybody.” Another UK physicist told us, “Well, so for me, science is not just a job. It’s a personal passion. It’s something I really care about. And I’m—I consider myself very fortunate to be paid money to do science.”

For these scientists, passion drives them, often overshadowing financial or career incentives. Yet this very passion can be perilous, making them susceptible to exploitation, burnout, and work-life imbalance. One UK scientist captured the dilemma vividly:

“You have to care about it so much that you're willing to put all of this time and you're willing to risk it all and spend ages looking for research grants, and risk running out of funding and all this kind of danger in order to do it.”

Civic calling: Science as public service

Other scientists frame their work as a form of public service. An Italian biologist emphasized science as a “mission,” extending beyond lab work to include popularizing science and improving public welfare. An Indian biologist concurred, arguing that science had to ultimately be an act of service:

“If you are only working in the lab without thinking of society, what is the benefit? Science should not just be about professional success but about making a difference in people’s lives.”

Here, the vocation to science is anchored in societal responsibility, providing external validation and societal relevance. However, scientists frequently lament institutional barriers—bureaucratic red tape, funding restrictions—that impede their ability to effectively serve society.

Transcendent calling: Science as higher purpose

A smaller group described their scientific work as fulfilling a higher moral, existential, or even religious purpose. A UK physicist eloquently articulated science as “the God-given toolkit for the ministry of reconciliation…building a flourishing relationship between humanity and the natural world.” Another US physicist told us:

“I felt like, and I still do, like this is my, this is something of a vocation, something that I've been blessed by God in certain gifts and talents that allow me to dive into these questions. Not everyone can, and that's a great blessing and gift that I should take on and to take advantage of.”

Not everyone expressed this higher calling in religious terms. An Indian scientist framed science a common mission for humanity—in fact, our most critical mission given the global crisis of climate change. Such transcendent callings resonate powerfully but can intensify personal sacrifices and justify overwork as moral imperatives.

Critiquing the cult of calling

While the idea of science as a calling remains compelling to most scientists, several of them also voiced sharp critiques of this narrative. For instance, a UK physicist highlighted the exploitative potential of vocation, noting how following passion led him to experience burnout “multiple times.” He went on to describe how departments run by scientists often lack proper management structures, allowing problems like harassment and workplace neglect to persist—and he thought the sense of vocation or calling might be partially to blame:

“I think it's because academic departments are mostly run by academics and they're focused very much. All these people that have been in academia have focused only on research, and so they don't really have management skill sets, and they don’t have people skill sets. A lot of the time for them, they want to focus on their research, and so if someone reports harassment or something, it’s easier for them to sweep it under the rug and try and make it go away than it is for them to take it seriously.”

Another compared the expectation of total dedication in science to a monastic order, lamenting, “It’s not sustainable physically or mentally…you can't have a life. It's like being a Jedi!”

The harshest critique came from a US physicist who argued that labeling science as a vocation implicitly justifies poor treatment. She passionately rejected the culture of overwork, calling it harmful and counterproductive:

“Any job styled as a calling secretly says people doing it are less deserving of respect. We say that about teachers and nurses, and we underpay them.”

Reimagining science as a vocation

Despite these tensions, the narrative of vocation endures, fueled by structural and cultural forces. Sociologist Erin Cech critiques the pervasive “passion principle” through which contemporary societies romanticize passion-driven labor, masking systemic inequalities and individualizing career risks. This cultural valorization makes calling narratives resilient, even as scientists increasingly face precarious employment and bureaucratic constraints.

Yet, my findings reveal that the ideal of science as a vocation in science remains deeply meaningful to scientists, helping them navigate tensions between intrinsic passion, societal impact, and existential purpose.

The persistence of vocation narratives in science raises urgent questions: Can we preserve the meaningfulness of scientific work without perpetuating exploitative labor conditions? How should institutions adapt to support diverse forms of vocational commitment—whether expressive, civic, or transcendent—while mitigating the downsides?

We urgently need to figure out how to answer these questions, not just for the sake of scientists, but for anyone concerned about the future of meaningful work in an increasingly precarious world.