This is a preview of my essay in Plough. See below for link to the full piece.

Around eight in the evening, I wrap up my toddler’s bedtime story and tell him it’s time to call Tata and Pati – his grandfather and grandmother as they’re called in Tamil.

The routine is the same every night. My father answers my WhatsApp call and shouts across the room to my mother: “Come, talk to the children!” It’s already dawn in Bangalore, India, where my parents live. My mother’s standing a foot away from the television, watching a live devotional broadcast from a Hindu temple. She needs glasses but never wears them, so she hunches toward the screen, eyes squinted. When my father calls again, she acquiesces and hobbles over to the phone as my father holds it out.

“Show me your toy – what toy you have today?” she asks my four‑year‑old in English. He hoists his latest Lego creation. Today it’s a spaceship with a red wing on one side and a blue on the other. “Mmm, very nice, very nice,” she says as he describes what it is. For three, maybe four seconds, her eyes catch light, as if a window somewhere inside her has opened. Then the shadows return. She turns away and tells my father in Tamil, “OK, take it away, take it away,” and goes back to the TV. We’ll try again tomorrow.

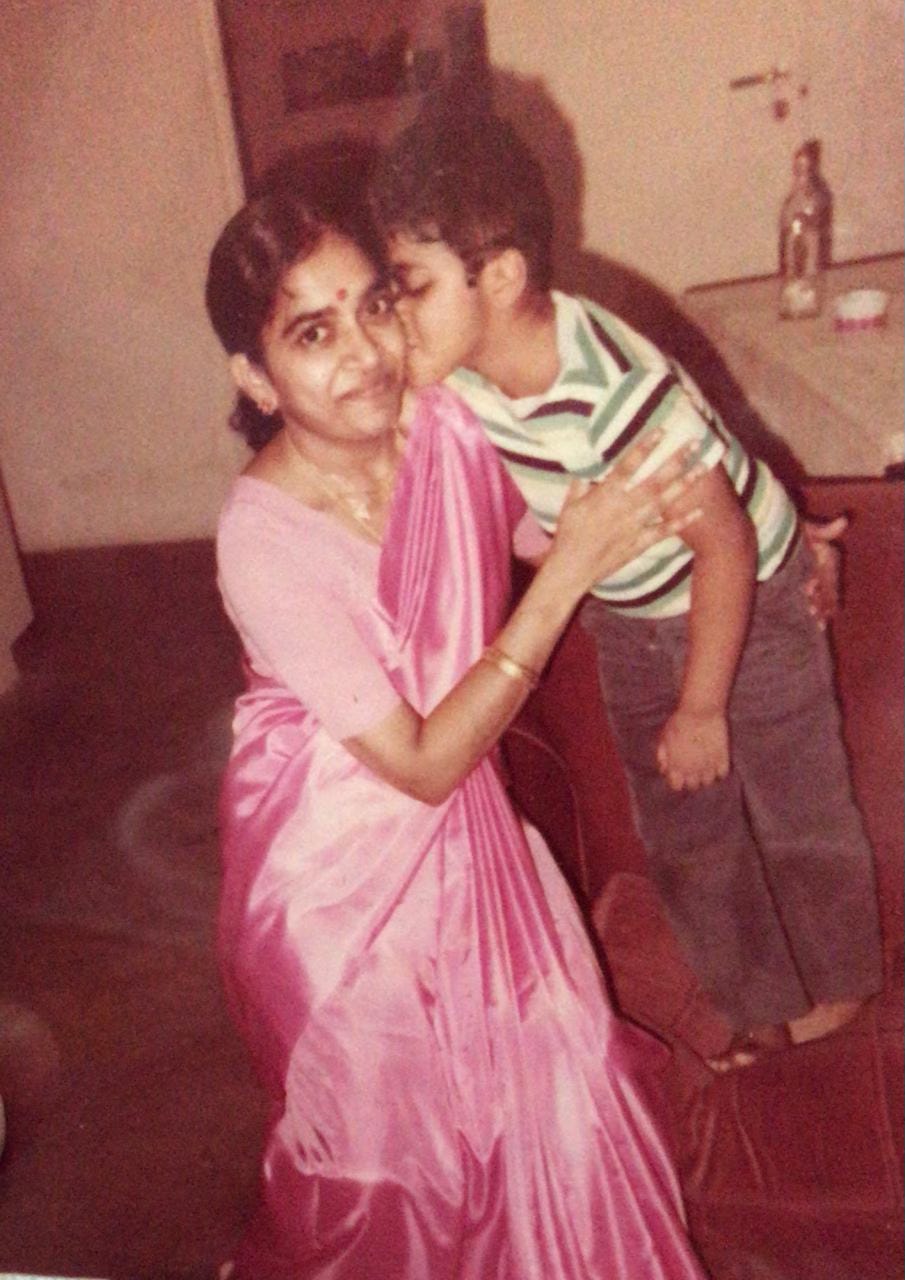

If you had asked me when I was my son’s age what beauty was, I would have pointed to my mother. In a photo from when I was four, I’m standing next to her, holding my green bicycle. I can still feel her running beside me in the desert heat of Oman, where I grew up: hand on the tall sissy bar, steadying the bike with one hand, and laughing as I finally figured out how to balance myself without training wheels. It’s one of my only memories of her being plainly, effortlessly happy. In another photo from those years, I’m standing on the couch and kissing her cheek while she beams at the camera. But I have no memory of that moment, or of ever having kissed her. Those kinds of moments would soon disappear as my mother became severely mentally ill. And as her schizophrenia progressed, untreated, what changed was not only her, but also the way I processed beauty.

There are two types of beauty. One is what I would call scripted beauty. This is the beauty for which we have cultural scripts – the kind we recognize and reward. We see it in physical attractiveness, beautiful objects, picture-perfect homes and doting couples and smiling family photos. Scripted beauty doesn’t have to be superficial; it can be laden with meaning and yearning, and its absence in one’s life can feel oppressive. The second is what I call revealed beauty – the kind that usually remains obscured, yet sometimes discloses itself unbidden in moments of radiance and recognition where something surprising breaks through.

It matters to be able to tell these two kinds of beauty apart. Scripted beauty has its place – it helps us stick to shared norms and orders our lives. But if we stop there, we confuse beauty with conformity. We end up wounding those who can’t follow the scripts, and become oblivious to their beauty. The worth of a person is never evident on the surface; it remains obscured from our eyes. And in chasing after scripted beauty, we lose sight of this deeper kind. We don’t know how to look for it – we may not even realize it’s there.

My mother, over a few short years, went from working as a physician to spending her days alone at home, gripped by a fierce worry, scanning the room with the intensity of someone who senses an enemy nearby, spending hours speaking to invisible presences. I never learned what triggered her illness. Her night shifts working alone at the hospital probably didn’t help; she resigned when I was six. Perhaps it was the long days subsequently spent alone at home, without extended family and friends, without the scaffolding of language and custom. Life in the Arabian Gulf as a guest worker can make anyone anxious – you’re always a foreigner, never at home, your visa one capricious administrative decision away from being canceled, forcing your return to a home country where stable work is even more precarious. Genetics, neurochemistry, and other unknown stresses were likely at work, but I didn’t know any of this, and couldn’t see it from the outside.

Read the rest of the piece at Plough online: https://www.plough.com/en/topics/life/beauty/my-mothers-hidden-radiance

This is exactly what I needed to read. Thank you.