Can Business be Beautiful?

At the turn of the 20th century, Frederick Winslow Taylor revolutionized the way people worked. It was an era of steam engines, factories, and relentless industrial growth, driven by a quest for efficiency. Taylor stood at its forefront. His new "scientific management" approach sought to dissect every task into its smallest components, timing and measuring each one to create the perfect workflow. A mechanical engineer by trade, Taylor applied his expertise to human labor, treating it like a machine that could be fine-tuned and optimized. Every second mattered, every movement was calculated. The result was a profound and permanent transformation in manufacturing and industry.

Taylor had humanistic motivations: he believed that maximizing efficiency and productivity would benefit both the employer and employee. But as the decades wore on, and the principles of Taylorism were adopted and amplified, a different picture began to emerge. The relentless pursuit of efficiency began to overshadow the human element. Workers increasingly became cogs in the machine, stripped of creativity, autonomy, and individuality. Factory floors became sites of deadening monotony and alienation.

Humanist critiques began to form in response to the reign of rationalism, raising questions about what was being lost in this brave new world of mechanized efficiency. The likes of Elton Mayo in the 1930s began to advocate for a more human-centered approach to management, recognizing the social needs of workers and the importance of cooperation and community within the workplace.

The pendulum swung back and forth over the decades. By the end of the 20th century, "Neutron Jack" Welch and others championed a new form rationalism, pushing for modes of re-engineering in which the person became ever more expendable. The age of computers and information technology only added fuel to this fire, making it easier to quantify, analyze, and ultimately, to control.

Yet, as we find ourselves in the present day, with Big Data and artificial intelligence shaping the modern business landscape, a new Romantic critique has emerged to challenge the new ratioanlism that governs business. Among its pioneers is Tim Leberecht.

Tim Leberecht is a German-American author and entrepreneur, and the co-founder and co-CEO of the House of Beautiful Business, a global think tank and community with the mission to make humans more human and business more beautiful. Previously, Tim served as the chief marketing officer of NBBJ, a global design and architecture firm. From 2006 to 2013, he was the chief marketing officer of product design and innovation consultancy Frog Design. Tim is the author of The Business Romantic (HarperCollins, 2015), which has been translated into nine languages to date. Tim’s writing regularly appears in publications such as Entrepreneur, Fast Company, Forbes, Fortune, Harvard Business Review, Inc, Quartz, Psychology Today, and Wired. His new book, The End of Winning, was released in German in 2020.

Echoing the late-18th century Romantics who pushed back against the rationalism of the day that stripped away the beauty, imagination, and emotion from life, Tim's new Romantic critique seeks to infuse business with meaning, beauty, and a sense of the sublime. In a world dominated by numbers, spreadsheets, and algorithms, he calls for a return to the human side of business, and further, to recognizing our humble role in the life-centered economy.

In our conversation, we talk about how his background led him to develop his Romantic critique of business and to co-found the House of Beautiful Business, a growing community that serves as a gathering place for thinkers, leaders, and innovators who believe that business should be more than just a means to an end, but an endeavor filled with purpose, passion, and creativity.

You can watch or listen to our conversation below. An unedited transcript follows.

Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts: iOS | Android | Spotify | RSS | Amazon | Stitcher | Podvine

Interview Transcript

Brandon: Tim, thank you so much for joining us. It's such a pleasure to talk to you.

Tim: Thank you so much, Brandon. It's great to see you again. I'm really happy to be here.

Brandon: Great. Tim, let's start with your background, with your childhood, growing up. What role did beauty play in your life? Because you have a mix of an artistic and business background, right? Your grandfather, I think, was a filmmaker and then your father was a businessman. Then you were a musician. If you could just talk through what role beauty played in your life through all of that.

Tim: Yeah, it's funny you asked that question, Brandon, because I'm actually in my father's, in my parent's house near Stuttgart. You can see actually. If I get out of the way, you'll see some photos on the wall. You can't probably see it, but one of them shows me playing the guitar. Because I played in a band called Migraine. The music was anything but migraine-sque. It was much very mellow, short song, soft jazz, singer-songwriter Tom Waits kind of stuff. I think I was 21, 22, 23 or so. We released two albums, actually. I sang and played the guitar. It was a wonderful time. That was the first time I think I ever really pursued something artistic. But even when I was younger, during my teenage years, I always wanted to be a curator, a publisher. I created fictitious magazines, fictitious TV shows. I did some fake sports commentary. I had a whole publishing group — an empire, in fact. I was always very interested in music and just creating stuff, creating other worlds, creating experiences.

It's funny that I came back to that just a few years ago or six years ago when I created the house, when I co-founded the House of Beautiful Business. I grew up in a very suburban, middle-class town near Stuttgart, which is the home to Daimler and Porsche and a lot of industry, automotive industry, Bosch. I mean, I have to be careful being in my parents’ house here. But it's not a part of the world that people would, on the surface, call particularly beautiful or idyllic, although it is very interesting. It's very Calvinist, and there's been a lot of philosophers. The car was famously invented here by Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler, the namesake patron of Daimler. So there's a lot of history here. It's a very industrious sort of Calvinist ethos, I guess, but also very creative. That's how I grew up — in a very safe, nothing to worry about, very privileged middle-class German family. My mother, my late mother, was probably the one who brought me to the arts and took me to classical concerts and valet, and introduced me to the beauties of a sentimental education, and the arts, and the knowledge that these arts contain.

Then I studied law. I just kind of shortened the long story. I studied law. Then through some digressions, I ended up actually in marketing. Marketing to me was like the most creative discipline of business. So from there, then I worked for a design firm in Silicon Valley for seven years. I wrote my book. I came back to my beginnings and the things that I was interested in when I was a teenager. I wrote The Business Romantic and then co-founded the House of Beautiful Business. And now I'm doing exactly — funny enough, I'm 51. I'm doing exactly what I wanted to do when I was 16. But it's taken me 30 years at least to, I think, muster the courage and acknowledge that that's really what I need to do and nothing else.

Brandon: What was it that you were trying to do when you were 16? You had this publishing empire. You were curating. Could you say a bit more about what was that? What was the seed there?

Tim: I think the seed was, I mean, I've read a lot when I was a teenager. I was very much into arthouse movies and the French Nouvelle Vague and independent movies and James Joyce. I've never read Ulysses. I read the monologue of Molly Bloom at the very end of it, and I've read short stories but never the full book. I was a very sort of heady child. I had friends, but I was also kind of a loner. I think I just sat in my room and created my own worlds. I wrote along I wanted to become a writer. I wrote screenplays and movies, but it was all sort of fictitious stuff. I had a radio show that my poor, little brother had to be a guest on. So it's funny how — I mean, I was a very imaginative child in a way. Then this is sort of, I guess, Sir Ken Robinson's thesis. We then lose this imagination of a child through our education and this rationalist view that is impressed on us. Then it takes quite some time to rediscover it.

Brandon: Yeah, talk about the origins of the Romantic ethos in your life. Was that a word that you identified with at a certain point and say, gosh, this is what I am. This is what expresses what I've been striving to do? How did that come about?

Tim: I never really consciously used it until I wrote the book, which I think I started writing in 2012. I remember that moment. I was working on the proposal with an editor and my agent. That was my first book. The book was supposed to be called Chief Meaning Officer. Thank God it wasn't published with that title in hindsight. But I realized that I was describing the principles of meaning-making as they made sense to me in business, in it through business. It was really an epiphany when I realized that all of these principles give more than you take. Dwell in mystery and mystique. Honor the silence. Lose yourself. Lose yourself. Surrender. There's others. I don't even remember them all now, but they were all romantic principles.

It struck me when I looked at them. It's like, oh, my God. These are all tropes of romanticism of the arts and literature, philosophy movement of the 18th-19th century that was a response to The Enlightenment. But I had never used that. I had never articulated that for me before even though when I was 16, 17, 18. I think I've always lived my life that way. So on music, the music we made with our band Migraine was very romantic. It was full of longing and heartbreak. Also, I remember the first city that I frequently drove to — because it's not that far from my hometown. It's a five, six-hour car drive or train ride — is Paris. So I've been to Paris. Paris — I really cherished and love. For me, it was just the most romantic destination and an escape from this rather gray industrial town that I grew up in and sort of the German, what I thought was a very stifling, narrow German psyche at the time. That's maybe how it all started — Paris.

Brandon: What inspired you to write the book? What prompted that?

Tim: The book was, I think, the result of many years of suffering in business, from law which I never finished. I never got a degree. Then I studied applied cultural studies, which was a crude mix of Wittgenstein and accounting. So I had business class and then I had philosophy. It was interesting. It enabled students to pursue a career in the arts or arts management or marketing. That's exactly where I am now. Then I worked in Silicon Valley for a while. It was in the beginning incredibly thrilling, eye-opening, and super interesting. It's competitive. I sort of felt like, oh, my God. This is the time of my life.

But after a while, I came a bit homesick. Silicon Valley became so just adamant and fervent about dataism — considering data the only truth — and this whole idea of solutionism based on this fact that you can engineer anything, whether it's an engineering solution, not only a software problem but a policy problem or a relationship problem. In fact, any problem in the world. That struck me as very myopic.

After a while in business, I think I realized and I remember actually that there was a meeting. I was the chief marketing officer at the time of the design company's parent group, which was owned by a private equity, by KKR, one of the world's largest private equity firms. There were at least a large investor. I was on board meetings. I love the adventure of it. I felt like a complete alien, an outsider. I loved observing it almost like an ethnographer. But I also thought: oh my God, these guys are brilliant. They're super smart, but they have absolutely no idea about culture and the tones in between, the nuances and how much damage they're doing also with a number of crunching mindsets to the whims and rows and nuances of culture, and how much value they're actually destroying by merging companies, behaving that way. I was sort of in awe but also really shocked.

Actually, I think that was the spark for me to say, after probably 10 years or so in executive positions, I need to now write down my truth. My truth is actually harkening back to where I came from. It's of somewhat European, probably sentimental, romantic truth. There is a space where I want to carve out a space for it in business. I began to write and give talks. I also felt encouraged by the fact that they were resonant. It struck a chord where people were interested in these ideas, which surprised me and then really, I think, gave me the courage to pursue this book.

Brandon: Had you encountered any examples? Because, I mean, often the response to that sort of critique is you're just being sentimental and naive. Business can't really run unless it's really Taylorian, right? I was really struck by the resonances in your book and in your talks about how so much of what you were responding to seems like a new Taylorism, the reengineering.

Even your new book around winning, I don't know if that word is in any way responding to Jack Welch. He has a memoir called Winning, or I think it's a biography written by his wife. Welch is, I think, the kind of prototype or the archetype of this new reengineering, the new Taylorism. Really kind of hyper rationalist, very anti-humanist in some way because you notice that he was called Neutron Jack. Because he would then go to buildings and destroy them and leave the people, get rid of the people and leave the building standing like neutron bombs. So it seems like there's this sort of a call for a new Romantic movement that emerges when there's a new rationalism that has taken hold. I don't know if that's accurate reading.

Tim: Yeah, I think that's quite accurate. I think that it's historically always been the case whenever the pendulum swung to a very rational, super optimizing, hyper-efficient mindset. When it became very binary in that sense, there was always this counter movement that was by and by design somewhat subversive. So I think the Romantic movement back then, and if there is one right now, it's coming from the pockets. It's coming from the underground. It's not a top-down framework that is an ideology. It's more of like pockets of resistance. That also makes it romantic, right?

Brandon: Yeah, were there examples that had given you confidence that business can actually work this way? It's not just a sort of sentimental reaction, but you can actually succeed in business by following these principles. Did you find any exemplars?

Tim: Yeah, first of all, it was definitely the company that I worked for at the time, Frog Design, which was founded by the legendary German industrial designer, Hartmut Esslinger. He had worked for Apple in the '80s and '90s. Steve Jobs — I heard many stories about Steve Jobs because they worked very closely together. It's interesting to figure in that regard because he is both in a way hyper romantic. Because he believes in the invisible, in the interior of products, and not necessarily in the metrics or the external metrics, at least. But at the same time, he's also a hyper-driven, very rational business mind. He was able to reconcile both of these somewhat opposing minds and still retain the ability to function, to quote Scott Fitzgerald. Frog was a place like that. It was very much because of the founder Hartmut. It was a very romantic, dramatic place full of adventure. It's also dark in a way. It was very hard to read. Every day when you went there, you didn't know what to expect. Now, that can be very off putting and unsettling but it's also I think, at least for me, at the time, it was a million times more interesting than a work routine that would have been boring and very consistent. I saw that as an example.

I also, for the book, then interviewed architects, startup founders. I spent time with Priya Parker, the author of the book The Art of Gathering which came out many years later, who had just started her practice. We both served on the World Economic Forum Agenda Council on values. We had many conversations about — there was always a conversation about ethics and doing good, and conscious capitalism and purpose. But for me, that conversation always struck me as still somewhat technocratic. It was very cold. I was always looking for the intimacy and the beauty that a novel, or a film, or any other piece of art might capture, and then express that in business.

I remember that I began to host events around a hackathon. That was still a thing in the early 2010 or 2011. It was called reimagining work or so that was with the World Economic Forum and some other partners. I think those were sort of early attempts to find the soul of business. I was inspired by the works of David White, the philosopher and poet who has written a lot about corporations and beauty in a way and corporations and meaning. I was attracted by culture such as Chanel, the fact that they onboard executives through a really pristine and sentimental education. It's really like honing their faculties, their sensibilities, embracing arts, and reading and interpreting the world and its supply and beauty, and developing a sensorial apparatus for that, rather than just being a skill-based functioning machine.

Then once I had that lands on, of course, what happens is, the world suddenly appears romantic to you. I see more and more businesses. I remember interviewing the founder of a series called Death Over Dinner that started in Seattle. It became a movement in the US, where people over dinner had conversations about the ultimate taboo, especially at work, which is death, and grief, and loss. It's also a theme, as you might remember, that we just covered quite extensively actually at our recent festival. I think all of these things came together. Suddenly, I realized, oh, my God. The reality that we were taught, that we were conditioned to embrace as the mainstream reality is just a narrow slice of what's happening. People want more. There is more. And now many years later, with the House of Beautiful Business and our work, the client work that we do but also the festivals and experiences that we put on ourselves, that's exactly what we want to create. We want to create a space to show the other side, the broader range of emotions of our humanity is possible in business. And it is.

Brandon: There's a lot in the romantic critique, I think, that's really important and valuable. I think it needs to constantly be brought to surface. The work I've done with scientists in many ways, I think. I've been studying the role of beauty in science. Many of the critiques of science are things similar to the critiques of rationalism. Because they're all about the reductionism — the stripping away of mystery and of beauty. Keats famously complained that Newton had destroyed the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to the prismatic colors, and so on. Keats himself, he was a scientist himself. He wasn't just a naive sort of wishful thinker. He was himself aware of the power and beauty of science. And yet, I think he was really concerned about the way in which relying exclusively on that reductive dimension can be really problematic. I think it's important too.

Even though scientists now have started pushing back and are more willing to talk about beauty and science more openly, it's not something they focus on. I think that's what needs to be brought to light — that even in business, even in accounting or even in Silicon Valley, there is a lot that is to be treasured. There's a lot of mystery, and there's a lot of magic even in the process of what seems like hyper rationalist engineering. It seems like your work is trying to shed a light on those aspects of business. Talk about the origin of the House of Beautiful Business. And even the word 'beautiful,' how did that come about?

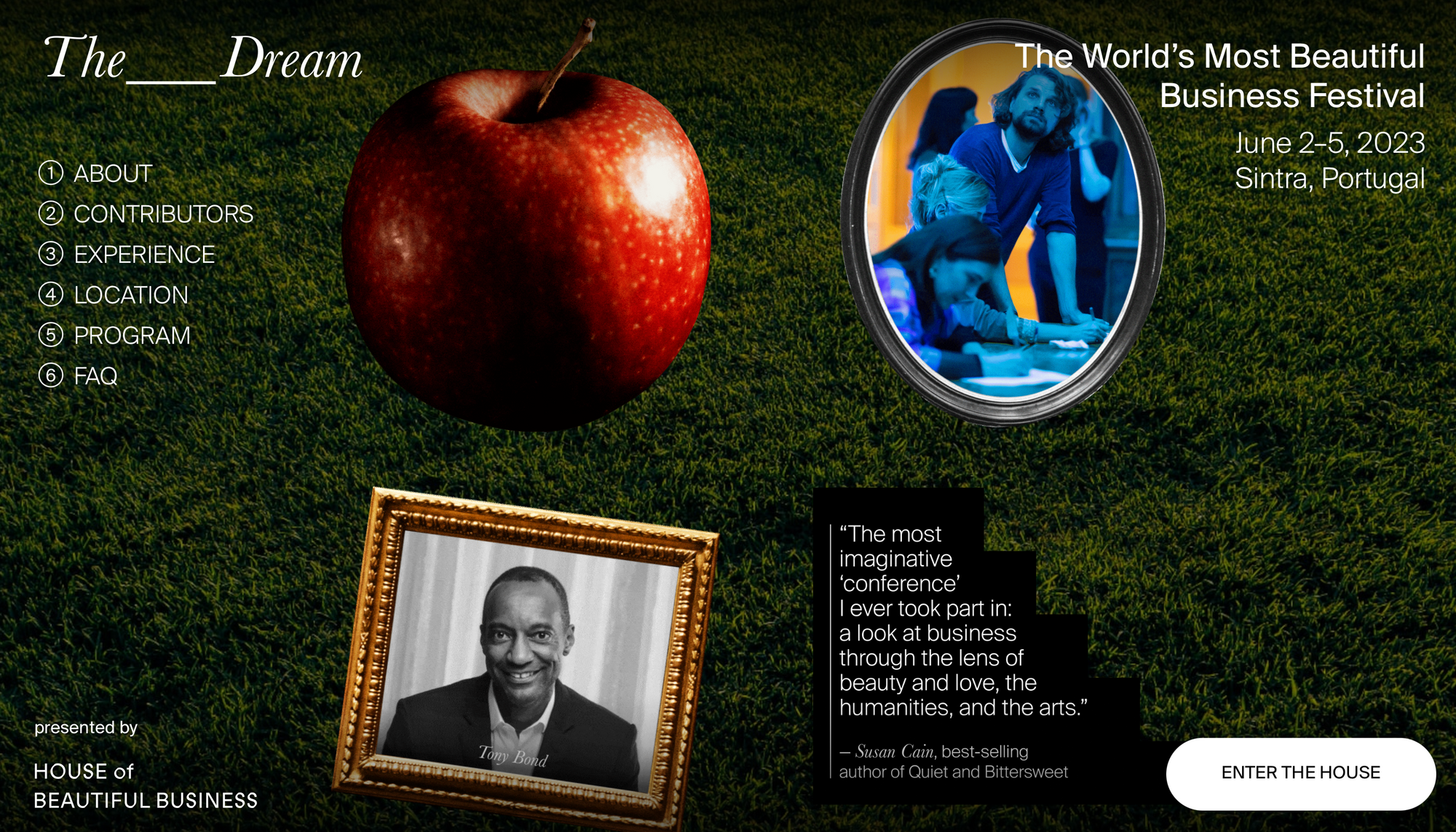

Tim: Well, I had written this book The Business Romantic. It came out in 2015. Around the book, I think there was an interest in forming a community. So I wanted to do an event. That was really the spark for the first gathering. My long-time colleague and friend Till Grusche, also a fellow German, our paths crossed again just at the right time. So we decided to do a gathering in Barcelona, in Spain. Initially, the idea was really to create the most romantic business conference in the world had ever seen, like the silent dinners, opera singers, exhibitions. Very different kind of programming but still this is, I think, a hallmark of the house, hopefully bridging back to the pragmatic and day-to-day needs of business. We don't want to be completely woo woo and out there, but we want to bring fringe and unorthodox ideas to an orthodox space without alienating I guess, to people who attend.

For that very reason, I think the term romantic, while being very useful for a book and the platform that I set out to build for this broader community, we realized it's too controversial or it's too polarizing. There are some people who read it as like HR departments. Oh, no. We don't want to be romantic, so I don't want to go there. Beautiful is just a broader canvas. Everybody wants to live a beautiful life. Everybody wants beauty. No one would ever raise their hands and say, "No, I'm not interested in beauty." So it struck us as a really great projection field. The house — we felt like we want to have a home for that, a sense of belonging. But why we were tempted, we think we never really fell prey to this desire to build something robust, an actual house, a physical building. I think the house is really a metaphor, and it must remain virtual.

And so we meet every day. Obviously, the team meets every day. Once a year, we meet. We host a big festival. We've now moved to Portugal. We did one online during COVID, and then we have a number of online sessions. We now call ourselves the 'network for the life-centered economy,' which is a term that we didn't invent. It's been around since the Club of Rome discussions. But it's so relevant and urgent now. It's a good one. It means that we want to create a business. This is maybe the definition of beautiful business. It's a business that honors all life around us and all life inside us, which brings to mind emotional diversity, cognitive diversity, cultural diversity, more inclusive, more fluid, more deeper manifestations of creativity and innovation and value creation. Then the very reductionist sort of movement and management theory have made us believe are possible.

The house has grown. It started as an event. It's evolved into a community of more than 30,000 people with more than 30 local chapters all around the world. A very vibrant community that is, to a large degree, self-organized. We see ourselves as — it's partly, I guess, a movement. I'm careful with that term. But it's a community that is actually I feel like quite real now after six years, that has really grown roots and branches and has a real body. It's real. I think there's intimacy there as the main currency. But we also produce a lot of thought leadership. So we publish a lot. We do reports, and we do a lot of client work. We work with many Fortune 500 companies, and we help them envision a life-centered economy. We help them map out what that might mean for them. We help them most importantly to create events, experiences, and stories that touch them, that really touch them on an emotional, not only on an intellectual, on an emotional and a somatic bodily level. That's a key lever for change. So yeah, that's where we're at.

Brandon: Fantastic. Could you talk a bit about the transition from human-centered to life-centered? Because I think that's one shift I've seen in your work. The other thing, if you could touch on, is just even if you could give one example of one of these organizations. You don't have to name the company, but just the kind of change that you've been able to bring about in trying to create this life-centered business.

Tim: The human-centered economy has been the holy grail for a while. I mean, it was like the lowest common denominator. Everybody could agree on human-centered products, human-centered experiences. IDEO, the design firm that was the main rival when I worked at Frog Design, really did a remarkable job in promoting design thinking and broadening the remit of design. It also really famously propagates the idea of human factors. So let's start with personas. Let's look at the human needs if you look at Maslow's pyramid of needs, of course. Also, maybe all the ones that are a little bit more subtle — the social needs that we have, the spiritual needs that we have — and then design for that based on this premise that the human is at the center of all things. That would inevitably lead to a more humane economy.

The shift that we have made, and I think the world is also making if I scan the world around me correctly, is this realization that that's just not good enough. It has led to so many externalities, whether that is our mental health, this focus on we need to optimize our humanity in a way and bring most of our humanity and bring it to work. It has led to a lot of disconnection and alienation from nature, from the other. It has led to the fact that I think convenience and comfort have probably been over indexed when designing workplace and product experiences. I think most importantly, of course, climate change and the climate crisis and the damage that we've done to our natural habitat. Also, I think this neglect for other life, other species around us, has partly to do with the fact that we've had this very human-centered myopic mindset.

The life-centered economy goes beyond that. As I said earlier, it acknowledges all life inside us. Not just the positive emotions, not just experiences that are designed to make us happy all the time but also workplaces that allow us to be sad, angry, inconsistent, and complicated, and struggling because that's who we are, and hard to read, and unintelligible. Then secondly, I think it's an economy that honors all life around us, as in heightening, expanding our consciousness, being aware of the cycles of nature, whether that's the circle economy or designing work more in a cyclical fashion where there's moments of rest, and harvesting, and recharging and rebirth and grief as nature tells us. I think those.

Also, I think a renaissance of the spiritual and the physical, the somatic, reconnecting with the soil, with the earth, with our bodies and the knowledge that it contains, not just the intellectual knowledge that we have in our heads and also with spiritual practices. It's a word that I would not have used five or six years ago. I didn't use it in my book. Now I feel like the business world is ready for it. We see it pop up.

You asked about examples of work. I just came back from a partner summit that we helped curate and host and produce for a big talent search consulting firm. They used human designs, human design as a framework that is based on Kabbalistic wisdom and other spirits. It's a hodgepodge, a mix of various practices. But essentially, it dissects and identifies the energy types of people. Then it helps leaders assemble teams and make staffing decisions and career decisions and strategy decisions based on energy. That's really interesting. It's more accessible than other spiritual practices, I think, because it has very practical value. We see organizations use that. We did with a big carmaker for which we ran a leadership session, we looked at auric cleansing — looking at the energy in rooms and things that have happened in rooms before they entered, and raising awareness of energy. It's something that is hard to quantify, but it's there. It's present, and it's a matter that affects how we make decisions and behave in business.

We orchestrate longer-term leadership journeys, where we then bring in speakers and we create experiences. We go to interesting places. We push people gently out of their comfort zone. But we also do interventions. We're actually doing one next week in London with a fashion brand. It's also a leadership development program, where we're playing with AI in what could make the AI more beautiful and things like that. So yeah, I think it's all what we call experiential thought leadership — taking ideas from disciplines that have been long neglected, bringing them into the arena of business but doing it in a very theatrical, immersive, entertaining even fashion so that it really is something that moves people.

Brandon: Yeah, that's fantastic. When I started out my undergraduate career, I wanted to be an engineer like most Indians who come to the west. I grew up in the Middle East, and I moved to Canada for college. Then I started out in engineering. I quickly switched to business, mainly because I was interested in understanding why people worked and the questions around why work is meaningful, and what does meaningful work look like. And so there were two kinds of questions there. One had to do with, is there such a thing as meaningful work? In a more philosophical sense, what is meaningful about work? Is there a purpose to work? Why do we do this? But then, who does it and how do they do it?

Those questions led me to what was then in the management literature a burgeoning series of journal articles on spirituality of the workplace. This movement had started in the '90s and still is pretty alive in the management world and in the academy. But even then, in the early 2000s when I was doing my undergrad thesis and so on, I was starting to see just a lot of concerns about the abuse of spirituality. Once you start to have companies leverage spirituality as a means to success, as a means to productivity, there are all kinds of prospects for abuse. I'm just curious to know how you see that surfacing. Because it's such an intimate and sacred part of who we are. A lot of people, on the one hand, want to be whole persons. They want to be really integrated. Other people want more separation to say, "I don't want my company messing with things that are really important to me." I'm just curious to see how that fits in the work you do, how those tensions emerge.

Tim: It's a real concern. It's one that we very often talk about and we're very aware of — this notion of bring your full self to work and be quite intimidating. It can be a tyranny of emotional performance, where you now are supposed to show up, and you need to be vulnerable. That became sort of a thing. It's almost like your performance is now measured on the grounds of how high is your emotional intelligence, your social intelligence. Can you be vulnerable? If you're not, what is wrong with you? Which is ironic.

I think the key thing is to just to give choices. Not everybody wants all of their desires and needs fulfilled by their work. They're quite happy with a 30-hour, 40-hour work week or less. Ideally, less. We've seen all the research showing that 3 or 4-day work weeks are quite conducive to better outcomes in business. I think that the choice is really important. I think ultimately because we spend so much time at work, 70%-75% I believe of our waking hours as knowledge workers, I think work, if you define it as an amount of energy devoted to something over distance, the question is: what do you devote your energy to if not work? And what is work to begin with? So it depends a little bit. I noticed that not everybody has this privilege of being able to even pursue the work that is purposeful and meaningful to them, and have their energy and the time they spent match in the best possible fashion. But I think we should, if we can, within the confines that are inevitably there, we should at least try.

I think what we're trying to do is just open up a possibility space. So if people want to be more vulnerable, if they want to experience emotional intimacy at work — by the way, we should also in this context mention the loneliness crisis. It's so latent and outrageous in a way. Workplace is, of course, more than any other societal institution, I would argue are sort of the secularization of our Western societies. They have the power and perhaps the responsibility as well to create intimacy.

We know that intimacy is the antidote to loneliness. It doesn't even matter whether it's a very close relationship to a very close confidante or friend. What matters is the small moment of attachment as to the marriage or relationship that researcher, John Gottman, says. So if you have a lot of micro moments of attachment in there, even with strangers, you have moments of intimacy. I think that can fuel you. That can mitigate any sensation of loneliness. Loneliness also comes from the fact I think that your energy and who you truly are is not really matched by what you do. I think that leads to burnout. That leads to stress. That leads to trauma. That leads to, I think, depression and to loneliness also, being lonely with yourself. So we try to do what we can. But I think we're trying not to become cynical.

Of course, you can always instrumentalize. You can instrumentalize mindfulness. You can instrumentalize the types of experiences that we create and then say, oh, this is all great because it's going to make us more productive, or it's going to help us make more money. That's it. Whatever it takes. If it's spiritual, great. Let's use it. That's, of course, a real pity. But I still think introducing these practices to business, no matter the intentions in the beginning, even if it's in the guise of enhancing productivity which is much easier for many managers to make a case for, once it's there and once the value is recognized, and once it's experienced, maybe my hope is it'll take a life on its own. Then it will develop so much momentum and force that this instrumentalism, disputed utilitarian mindset, might be overcome. I think that's the hope that I have at least.

Brandon: I don't think having workplaces where people feel sort of spiritually manipulated is a good thing. On the other hand, you have often workplaces that are rife with loneliness, that they're alienating and dehumanizing. That experience doesn't need to be there either. I know there's increasingly this desire. I think the success of the recent book The Good Enough Job, Simone Stolzoff's book, I think speaks to the fact that people are realizing that maybe this pursuit of work as the be-all and end-all the kind of workism — the expectation that work should fulfill out every aspect of my life — is not working. But at the same time, I think that the alternative doesn't have to be that the workplace is really the kind of Taylorist in a rationalist alienating kind of workplace either.

I do think though that one of the things that occurs to me — it's the same in not just the workplace but in the university — is that you have people coming to you who are really struggling with loneliness, with mental health challenges. Part of it is that I think a lot of our social institutions have stopped functioning. Families have stopped functioning well. Schools have stopped functioning well. And so we've recently been having some debates at our university as to whether what is the purpose of the university anymore. Are we simply about a space where people download some knowledge into their heads, or is this a space where people need to learn how — should we be spaces of hospitality?

I've been trying to think about what it means to create classrooms that are spaces of hospitality and encounter, rather than just a place where you go and passively consume some knowledge. Partly because I think people are not capable of learning unless those basic emotional needs can be met, unless they can feel a sense of psychological safety, and that somebody here is invested in their well-being. So I think even with work, it's one of those things where I don't think you can really bring yourself. Even if you're drawing rigid boundaries around work and saying, "I'm only going to work 20 hours a week or 30 hours a week, and I'm not going to bring my full self. They don't need to know who I am," you still need to experience I think a sense that this is a space of hospitality where I'm welcome.

I'm just curious about the role of hospitality then, but also about whether you see business as a surrogate institution in some way in providing what maybe other institutions and associations are supposed to provide. But those things don't exist or function very well. Families don't function well, or sports clubs don't seem to function well. Is it the job of business then to provide that?

Tim: Yeah, I mean, they're still answering your question. I think those are really interesting observations. Looking at our own team, many of our colleagues are Gen Z and Gen Y. They have stopped looking for meaning only at work or the formalized work. Many of them have very flexible setups, and they have passion projects on the side. They have a side hustle. It's not even a side hustle; it's just another work activity. So I think the notion of work has become much more holistic, and it's no longer tied to employment or to the one thing that defines you, that grants you identity, that you do. I think that's really important.

It's also important that we do work even if we are not working. I'm thinking of, for example, the whole Rest Movement — Trisha Hersey in Atlanta, The Nap Ministry and sort of napping and resting as resistance to this pressure of constantly having to perform and to advance your career and to optimize. I also was just reading The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran and his really beautiful letters to Mary Haskell. She writes back to him and says, "I want you to know that even if you're not writing, if you're not producing something, you're always working." Your silence and the pauses and the times in which you don't work but reflect, they are your work. They are your life's work, perhaps even more than what you actually produce. Now, that's an artist. That's a very different life reality. But I do think that we need to begin to understand.

The right question to ask is: what is our life's work? How much of that is in employment? How much of that is as parents? How much of that is as a friend, as romantic lovers and partners? How do we manifest ourselves? How do we bring what only we can bring to the world? That's the work we have to do. It can be various platforms and channels. This brings me to the question you had about hospitality. This goes back to Priya Parker's work as well, who asked this question, what does it mean to be a good host? She also asked, what does it mean to be a good guest? But since we talked about hospitality, what does it mean to be a good host? It's a good question for business leaders and organizations, not only for the customers, in relationship to the customers but also their team members and society at large. How can we be a good host, and what does it mean to create hospitality?

Now, the one thing I would say about classrooms and at universities is that, I think more than anything else, I would argue that, yes, they need to be temples of hospitality. They need to create a sense of belonging. But I think that belonging is not the same as fitting in. Belonging is probably quite the opposite of fitting. It means that you can be who you are without the need to fit in and to attune. I think the one thing that I appreciated about going to high school and then in my post grad or master's degree in Los Angeles is, I think the one thing that school or education students can provide is their spaces where we can learn to disagree. I think it's not just about validation, but it's actually like let's learn how to fight the good fight, defend our views, and change our views and battle, and have debates, and learn to disagree respectfully and still have a relationship to someone who's maybe not like-minded. We don't have enough of these institutions. So I think that's really, really important. I hope that we don't design that out of the system in an effort to produce functional, employable individuals who are cogs in the wheel and work for the machine, but rather we help people individuate and find their true selves to then do what is their life's work.

Brandon: Yeah, that's really brilliant. It is so necessary in our polarized times. We want to sort ourselves into our camps, into our little bubbles where everybody believes exactly the same thing. We don't really know how to be with people who disagree. I was very struck by the festival that you hosted, The Dream. That was this year's festival of the House of Beautiful Business. I was only there for a day, for about 24 hours. And yet, I think that it was probably the first experience I've had in maybe some 20 years where I could quickly connect with complete strangers and really build genuine friendship. I've made some really wonderful friends there whom I'm still in touch with just from that one day. I'm still in all of what you guys did.

How did you create this experience? What is your secret sauce? What's the principle? What are the kinds of ingredients that go into creating something like this? I don't know what stands out to you as what it would take for others to do something like this. Because for me, it was such a beautiful experience, and I'm still in awe of the ability to create the context in which these kinds of genuinely human interactions and intimate connections can happen.

Tim: Well, thank you so much, first of all. Brandon, that really means a lot. Thank you for coming over for one day from DC, I believe. That was quite a commitment. I believe, at the end of the day, I can give you some specific beliefs that we have and experiences. But I think at the end of the day, I think it works because our heart is in the right place. That's what people sense. The people who come, they come with genuine interest in one another. Not a transactional agenda.

There's a few things in which we manifest that or that might help create that kind of context and environment. One is that, as you may have noticed, we don't have name badges. This is in an effort to avoid that people look at their name, their badges, and trying to figure out whether it's worth having a conversation with Brandon. Because he's not a CEO. What is in it for me? Of course, that's a real pity. Because often we discover things, or we basically prevent ourselves from discovering things that are quite important, and then strike friendships.

Business is always a byproduct of our gatherings, but it's never the foremost purpose or reason why people connect. They want to connect because they want to get to know each other. They're interested in different views. We didn't have screens at the event. We tried to design times of decompression and nothingness, where people can just sit still and connect with each other and have longer conversations. We challenged their views. We inspire. We bring music, the arts, dance, and other experiences into the mix. But I believe, at the end of the day, it's really the intimacy and it's the genuine intention of the people who are there. This is also a community that has grown over six years. This was your first time, but many people have been there for two or three times. Everybody's quite open. We want to be very kind. It's really important to us that this is a very kind community. They're very welcoming, very warm.

Communities always start — as I think a famous sociologist, whose name I forgot, once said — as pseudo communities where there's a mission and declaration of intent and shared values. But then it takes a while and usually a crisis or real challenges for communities to become real. So they become really a body and vibrant and alive if they've gone through some crisis together, if they've been tested. We had some of the social experiments. COVID was a big factor in that regard. It really brought people together and helped us grow the community. That's the key question for us: how can we maintain that intimacy? And yet we want to also grow the community and scale it. The depth, of course, is an interesting tension.

Brandon: What does success look like for you in terms of this? Or maybe that's not the right word. But how would you know that this is on the right track or that you've been doing the right thing? Again, I don't want to make this a technocratic reduction to metrics of some sort. But there's this probably something you're trying to use to gauge whether you're doing well. Maybe the growth is one aspect of it, I suppose. But how would you ultimately know that, yeah, this is really what we wanted to do. Look, it's happening?

Tim: It's definitely the growth overall. We look at, are we expanding our footprint? Is there a resonance in other markets? We're exploring. We're actually going into a different continent also with some of our events next, next year beyond Europe, in the US. I think that's one thing. We're quite enamored by these local hubs and just the amount of activities there. So that's a sign that there's a certain stickiness. The fact that people stay in the community, and then sometimes they do less, they drop out and then they'll come back and become a little bit more active. That's totally fine. But I think most people, once they're in the house, they value the connection.

Secondly, we do all this stuff like net promoter scores. We do surveys. We look at whether that's in our client work or the festivals that we create and the events that we create. We also look at retention scores and satisfaction scores. With the client work and the work that we do inside organizations, we look at repeat business. We are very keen on moving beyond the intervention. Once we intervened and we staged one experience that we have champions in the organization that helped us, it just really grows our footprint there and influence them.

What I would love to see with my co-founder and I, and I think our community would love to see, is just much more influence. I think in a sense, we want to be a more recognized voice. Let's take generative AI in the future of work in light of generative AI. Can we develop a point of view? Are we a community that can bring something to the table that is not part of the conversation yet, but that needs to be heard? Can we bring the talent, the very unique, eclectic talent that is in our community? Can we bring that into organizations in a much more concerted way? Can we infiltrate these organizations? Can we create more change-makers and ambassadors within these organizations? Can we really become a movement that is producing very interesting, very unique, genre-defying work that will be remembered and that encourages people — I love this word courage, because it comes from heart — that gives people the heart to live their business life differently, and then themselves become more courageous and inspiring others?

It's hard to quantify. We do have some metrics in place of course also because we have investors. We're a business; we want to grow. We're quite ambitious. We're encouraged by the recent festival a lot. I think that was great to see how people responded to that. But as I said earlier, I think the challenge is also, how do we grow this without commodifying and still being very intimate and very special, and also the sort of rebellious subversive spirit that is also part of our brand?

Brandon: Yeah, I think it's super important work you all are doing. Because I think, ultimately, for a lot of people, the temptation is, especially for the business world, to make everything about profit and about success. But business is a means. Business is a way in which you bring something valuable into the world and which you solve a problem. I think that can be a means to also enhance our humanity too, to bring that to the fore rather than crush it.

Then too often, I think when we lose the focus and get our priorities wrong, I think it ends up dehumanizing us. That's a lot of what we're seeing, I think, in the work world, where people instead of making profit of the means, it becomes the end. Then it starts to lead us astray. Talk about your new book. What are you working on, and what are you hoping to do?

Tim: It's just been such a struggle, Brandon. It's one of these projects that had a lot of false starts. It's a difficult birth, which also shows me that — it's funny. I was recently at a dinner, and I said this book is just not going to come to pass. I don't know what it is. I just don't have time for it. I never find the time for it. That person basically turned to me and responded and said, "No, basically, you're not ready for it. The idea is maybe not there yet. It's not the time thing." I think both is probably true. It's a difficult birth.

The book is about mysticism and management. In a way, it's a continuation of the journey that I started with The Business Romantic. There I delved into the romantic world, the world of exuberant and unquantifiable emotions as an added dimension, as an uncovered dimension, an under covered dimension of business. But even that now strikes me as maybe perhaps too shallow. I think what I'm now interested in is, let's go even deeper into what I mentioned earlier, the subconscious, the unconscious, the spiritual side of our being. Really the mysterious mysticism aspects of being. There's so much knowledge in that.

What I've observed also for the work at the house and the people we curate is that there's really been a trend towards that. I think what I'm struggling with quite frankly — I'm working on the proposal now. I've interviewed a bunch of people. I'm just creating a body, like a table of contents and some drafts. But it's been really going on for almost like one and a half years now. What I'm struggling with a little bit is that I'm not really engaging in these practices. I'm more of a keen observer who's very curious about them and interested in them. And so I think I'm struggling a little bit with how personal I want this book to be. Is it a reportage? Am I just calmly observing what's happening and interviewing people? I do think because it's been such a difficult birth that I'm going through this transformation. It is a very personal project, and so it needs to come out. But I think that probably needs a bit more time.

Brandon: Well, thanks for sharing that. I do hope that it comes to fruition, because I think it's very important. I think whatever journey you're on, I think it will benefit all of us. Tim, thank you so much. I'm so, so grateful again for this interview, for this conversation. It's been such a pleasure getting to know you a bit more. Where can we direct our viewers or listeners to your work and to what you all are doing?

Tim: The best destination is the House of Beautiful Business website. It's at www.houseofbeautifulbusiness.com. Google it. Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter called Beauty Shot. That's a good window into the house community. Join one of our online sessions. Read up on us, and come join us. You could come to one of our events. The door is open of the house always.

Brandon: Fantastic. Yeah, I highly recommend it. Do you have a tip of some sort for any of our viewers and listeners who might want to infuse more beauty into their work life or to make their business more beautiful, one point that you could leave them with?

Tim: Two points. One would be, just take them. Take your team. Take them to a concert, a movie or a theater play, and then let that sink in. Then talk about it. Take the time to talk about it. You'd be amazed how such simple endeavor will actually open up new perspectives and actually change the relationship you have. The second tip I have is silent dinners. We've done many silent dinners with clients. There is something so powerful about dining silently for 90 minutes with colleagues or strangers, not saying a word but actually connecting on a very deep level. Everything will change after that, I promise. I promise you those are fairly easy-to-pull-off activities that I highly recommend.

Brandon: Wow. When I was an undergrad, I used to visit a monastery to get a break from my studies. It was an instituted practice that the meals would be silent. It was quite an experience every time. Fantastic. Thank you, Tim. Really grateful.

Tim: Thank you so much, Brandon. It's been a pleasure.

If you found this post valuable, please share it. Also please consider supporting this project as a paid subscriber to support the costs associated with this work. You'll receive early access to content and exclusive members-only posts.