How Art Can Transform Us

If you visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in London recently, you might have come across the Firefly series by Yael Martínez. In this series, the artist uses photographs to represent the impact of violent trauma on his family and community in Mexico. Martinez created small holes in these images, allowing light to shine through, symbolizing how trauma leaves a lasting impact, but also how we can transform our darkest experiences into light.

As psychologist Laura Blackie notes, such works of art poignantly convey the possibility of post-traumatic growth: the ability to find positive psychological changes in our identities and worldviews through their struggles with trauma. Art is extraordinarily powerful in helping us communicate and processing traumatic experiences.

My guest in today's podcast helps shed light on this transformative power of art. Wayne Brezinka is an award-winning mixed-media artist known for his unique and emotive style. Wayne’s signature style of art incorporates assemblage techniques applied to discarded and repurposed materials. He has been a contributing artist to numerous publications, including The Washington Post, The New York Times, POLITICO Europe, and others.

In our conversation, Wayne shares his personal journey as an artist, from his childhood fascinations to the challenges he faced in pursuing art as a career. We explore the intricate process behind Wayne's art, where he combines various elements to create portraits that not only represent the physical likeness but also capture the complexities and stories of his subjects. Wayne talks about beauty in art not simply as a visual aesthetic quality; there is profound beauty in the potential of art to help us engage with deeper emotions and questions – in the way it pulls us out of ourselves and leads us deeper into ourselves.

Wayne discusses his creative process and vision, including how his work helps him connect with his inner self and the larger mysteries of life. He emphasizes the power of art in evoking emotional responses, sparking conversations, and serving as a tool for healing personal trauma.

Here are some key takeaways from the episode:

1. Art is a calling that brings a sense of aliveness and connection to oneself and something greater.

2. The journey of an artist is filled with ups and downs, but embracing the tension and uncertainty can lead to growth and new opportunities.

3. Creating art is not always about making something beautiful, but about engaging viewers in deeper reflection about their humanity and the mystery of existence, and connecting them to something beyond.

4. Art has the power to open people up, spark conversations, and connect individuals to their own lives and experiences. It can give voice to personal trauma and create a safe space for healing.

5. Engaging with art and embracing the discomfort of the creative process can be transformative and deeply rewarding.

You can watch or listen to our conversation below. Please take a moment to subscribe and leave a review, since it helps get the word out about our show. An unedited transcript follows.

Also, if you haven't seen it yet, check out my new workbook which can help you design a more beautiful work life. Start the new year on the right foot and commit to finding and cultivating more beauty in your work today.

Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts: iOS | Android | Spotify | RSS | Amazon | Podvine

Interview Transcript

Brandon: Wayne, thanks so much for joining me on the podcast. It's such a pleasure to see you again.

Wayne: It's wonderful to be with you. Thank you for the invitation.

Brandon: Yeah, Wayne, I think we first met in — was it 2018, I think, at a retreat where you lead an art workshop? I remember that because it was a scary experience for me. It probably is for a lot of people who do your workshops, where I, as a kid, loved sketching. I really enjoyed sketching. I was really good at it. We'd do movie posters of Bollywood movies. Kids in my class would make requests for me to do this or that. But I sucked at anything requiring scissors or glue, or multiple paints. You had us do these collages that brought back a lot of bad memories. But it was a good experience nonetheless. I feel like I don't quite have that kind of coordination that some of the other kids loved the crafts, that they were really into making things that required more complex skills. I'm curious to know just your own childhood and the role of art in your childhood. What was that like?

Wayne: Well, first of all, thanks for having me speak with you and your audience. I'm nervous, to be honest. I've been kind of not wanting to be here, in a way that I think if I, in my head, share that with people, they can't relate to it. But I'm going to just be honest and do my best and share my heart with you and the listeners.

As a child, I think we're all born artists. We all come into this world with the creative gift and can create and dance and do creative things before we can speak. So I really believe that we're all born artists. And so, with that in mind, I was drawing and using my crayons at a young age in kindergarten. In fact, there's one story of me not finishing my coloring assignment in time to go to recess, and I was completely fine with that. All of my peers were outside on the field playing, and I was inside finishing my coloring assignment. But yeah, I think as children, we don't really understand. I didn't understand the why or the reason or have the tools to sort through logically why it drew me. But it pulled me in, and it still has me in its grip today.

Brandon: Wow. And did you know as a child, I mean, as you were going through middle school, high school, that this is what you wanted to do, to be an artist? Were there other things you were pursuing? What was your trajectory like?

Wayne: Well, I was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Then my family and I moved north in the country, which is about two hours from Minneapolis. And so I grew up on a gravel road, in farm country. In going to a school that had 400 children from kindergarten through 12th grade — there were 39 kids in my graduating class, and so art for me in that community was — I had this battle in my head of it not being well-accepted in such a small farming community and looked down upon and not really understood. So I had this shame rattling around in my head about pursuing art and then not being masculine or not being a part of the community type thing. But I still pushed through that, and I still pursued and followed its calling, if that makes sense. What was your question?

Brandon: You're answering it. I mean, it's just how you got — did you know you wanted to be an artist? And perhaps you talked about it as a calling. I mean, what was it like to feel? What did you feel? What was the calling? When did you feel it? What did that look like for you?

Wayne: I always felt, and I still do today, I feel alive when I'm making something. When I'm creating, I feel connected to myself into something bigger, some other — whether you call it God, or the universe, or whatever. I have this visceral feeling in my body as I'm making something that just lights me up. And it's in those moments. They're fleeting. They last for a few seconds or maybe a minute. But I understand in those times that I should keep going and keep doing what I'm doing, keep using this gift, if you will. And really, as of late, I believe that's why I'm here on the earth. It's to make and create and to point people to beauty, point people to something outside of themselves that might connect them back to themselves. And art, I think, is a beautiful way to do that.

Brandon: Yeah, that word beauty, did that mean much to you as a kid or as you're growing up, recognizing that this is somehow important to you? What did that look like?

Wayne: I didn't really think about language the way that I do today. I'm an avid reader of poetry today. The language and poetry, it's been said you can't argue with a poem. The language is, it is what it is. You feel something, or you just met something while reading it. And so, as a child, language — again, in the farm community — it didn't really hold as much weight I think for me as it does now. I think I'm blooming and growing and just opening up in so many different ways. I'm 55 years old, and I am astounded at the growth that's happened for me in the last 10 years, which I love. I feel very alive and content and open in ways that I wasn't as a child or as a younger person. And there's regret for not feeling and being this open now, having not been that way as a younger person. But I didn't understand, I didn't know different.

Brandon: Did you face any sort of opposition? You mentioned that it was sort of wasn't taken very seriously. Did it require a lot of courage on your part to invest in becoming an artist? What were your parents' reactions like or others in your family, in your community, to your pursuit of this path?

Wayne: I think it was encouraged. It wasn't discouraged by any means. But it also, I felt — it wasn't voiced by people. But I felt by my peers in school, particularly like a questioning, this energy from them was like, what? They're all in football or track or on sporting events or whatever. But my parents, my father actually taught me how to draw. When I was a younger person, maybe 7, 8, 9 years old, I was drawing a portrait of some particular person. I remember him sitting down and helping me look at the reference photo that I was using in the drawing that I was making and showing me how to construct certain features of the face. He's got the gift. He's got the creative talent. That's where I get it from. It's my father. My mother is also very creative as well. So it wasn't necessarily discouraged. But I didn't feel like it was this over encouragement of this is a vocation possibility for you. There was not that. That came from me just investigating possibilities of how can you make a living in art. Is there a way to do it?

Brandon: What was that like for you? How did you go about, I suppose, getting started as an artist?

Wayne: After I graduated from high school — well, first of all, I exhausted all of my art classes in high school by the time I hit ninth grade, so I was not able to take any more art classes pass ninth grade. So I absolutely loved it. When I graduated, I worked for a year. I put myself through — I saved up money and put myself through a vocational school. I went to a two-year 18-month program for graphic design. That was at the very beginning of the computer entrance into the world. We were learning computer programs on how to use the machine as a tool to design, which was very awkward in the early '90s. I graduated, and then I got my first job as a graphic designer at an advertising agency. My old life is a designer for book jackets and letterhead, cover letterheads, and business cards and logos and things like that. It just has opened up. I've never really known where I'm going, which is kind of the beauty of my career. It's I just go well. I think I'll step over here, and things open up. Or I'll go over here, and things open up. It's just following that feeling of calling, I guess. There's that word again.

Brandon: So you were working in the advertising world as a designer. Then at what point did you break out on your own and start working as an artist full time? What was that transition like?

Wayne: I graduated from high school and moved up north in Minnesota. I still stayed in the state of Minnesota for a few years. I worked at the advertising agency up in Duluth, Minnesota, right on Lake Superior, the northernmost part of the state. I've been fired a few times in my life. And so that was one of them. I was very social, like a butterfly bouncing around from everybody's office with my coffee, wanting to know how their weekend was and what they were doing. Then it didn't go very well, because I wasn't working to the way they felt I should be producing. So I moved back home to my parents. I had this desire to move to Nashville because that's where the music hub was at the time. It still is. I love music. I've always been passionate about it.

Brandon: Do you play as well?

Wayne: I don't play. I played in high school the drums, the clarinet in high school band. But I don't play in terms of, or sing. I visited Nashville a few times with the intent of discovering or hoping to land a job at a record label, to do record album package, in the early '90s. And after my third visit here, I thought, well, the only way to actually find out is to make the move and see if I can make it happen. I packed up my blue Oldsmobile. I call it my grocery getter in 1993. I put all of my belongings in it. It was really difficult for my parents and my family at the time for me to move so far away from them. But I just took the risk and made the drive and moved in with two people I didn't know. My world opened up, from this small little farming community into a large city, which was scary as hell for me but a little kick in the pants to just see the world in a new way.

I wasn't here for about three months and landed my first job at another advertising agency doing book jackets, and logos, design for banks and things like this. I was appreciative. I enjoyed it, but I didn't really — it didn't light me up. I still had the desire to do album packaging. At that time, I met my wife at a church here in Nashville. We were at some function. You know when you're talking to somebody — I think I maybe mentioned this to you before — in a roomful of people where you're looking at that person that's in front of you, but you're actually listening to the conversation behind you? You're nodding and going yeah to the person, but you're really connected back here. Well, the woman that was behind my ear was the creative director for one of the record labels that I wanted to work for. I overheard her say that they had a position available. They were looking for somebody to hire. I kind of flipped out.

The next week, I think she called me and said, would you like to interview for this position? We had become friends. Her and her husband, and Stacy and I, my wife, Stacy, we were hanging out for dinner and enjoying each other's company. I said to her, I said there's only one. Under one condition, I said. And that is if I'm the right person for the job. Don't hire me because we're friends or that you know me. I said I want to be qualified for the position. And so, thus began the interview process. And I got the job. It was probably the funnest. I mean, we played practical jokes on each other. Our little creative office was shut off from the rest of the corporate record label. And so we would pull pranks on each other and just have the best time.

This is all going somewhere to your question. I was there for about four years. One Friday afternoon, I get a knock on my door. I had a real swanky office. I had big picture window, furniture. It was super nice. My door was shut this Friday afternoon. And so I get a knock on the door. It's my boss. She says, do you have a minute? I said sure. So I get up and walk out. In the entryway of the creative services department were my colleagues. They were all kind of congregating at the reception desk which, on a Friday, that's what pretty much everybody did. Because they were ready to go home. It was about 4:30 in the afternoon. Her office, her door opened in. She had already walked in. She said, do you mind shutting the door? And so I walked in. My heart's beating. I'm like, what is this going on? As I shut the door, behind her door was a table. And at that table was her boss. She says, have a seat. I said, oh, man. What's happening? So they proceeded to fire me.

They told me why. They gave me three reasons why. One of the reasons — well, all of them. I had never heard these three reasons prior to that meeting. One of them was, they said I was not providing the marketing team with what they were requesting from me, the services they're requesting. I mean, we kind of bump heads. But that's part of working. Things didn't go. She said, we need you to pack everything up and leave today. I said there's no way. I have too much stuff. I can't fill my little Toyota Corolla car with all my stuff. Can I come back on a Saturday? She looked at her boss and she said, yeah, we can work that out. So she met me there with her husband. Then I brought a friend of mine with me to pack up all of my stuff on Saturday.

I share this when I teach my workshops. I share this story with my students sometimes. I had the last box of stuff under my arm, and the other hand was on the doorknob. But she was on the inside of the door. I turned around and I said to her, I said thank you. I said, this has been the most incredible job that I've ever had. I wish you well. Then I left. But I can't tell you what in me caused me to say those words. But what I learned in hindsight after a year or two later was that, often in life, how we exit a situation — whether it be a relationship, a marriage, or a friendship, or a job — speaks far greater than how we enter. And so the posture that you carry when you leave a situation is what I learned. It was almost intuitive or an instinct that I had. It wasn't something that came out of my mind. The following week, she called me back to freelance as a freelance artist in the same office, which kind of blew my mind. But it was at that time, an answer to your question, that I began to put my foot further in fine art and illustration, if you will, for some of these publications that you mentioned at the top of the interview. It slowly began to open up for me after I was fired for the second time.

Brandon: Wow. Did that feel like prompting to sort of do things on your own? Because going from the stability and security of a job or getting a paycheck to freelancing, how was that transition? Was that difficult, or did you feel comfortable? How did you go through that?

Wayne: It was very difficult. It was very stressful. What they didn't know, the folks at my job that I was just fired from, was that my wife and I were pregnant with our second child. None of them knew that at the time. So she was great with a child. And here I am coming into the house that we just bought, and I said I lost my job. It was very stressful. But the only instinctual thing I knew to do was to freelance and just put my name out into the pool of local Nashville people. I soared. I mean, it just took off. I mean, I did better as a freelance graphic designer than I did working for a company. So it all worked out.

One of the things I've learned lately is that, and I don't think young, it takes a while for people in general to understand that in life, there's tension. There's this tension of unresolved issues. And when you can understand that that's life and if you can live in balance on that tight rope with unresolved issues, you're going to do great. You hold your arms open to the unknown rather than demanding an answer or demanding closure for something. That's really not how life works. But it's helped me tremendously lately to understand that somehow it's going to unfold. It'll work out. But at the time, when you have a second child on the way — I was in my 30s probably — it's much more difficult to understand that.

Brandon: Right. Wow. So what has this journey been like for you the past couple of decades? How would you characterize that? The work of an artist, what is it like?

Wayne: Well, I'll tell you this. A lot of people from the outside looking in — my neighbors, friends, people that come up to me that maybe have been familiar with my work — they say, oh, wow. You get to make art all day. That must be amazing. What a great job. I kind of half smile and I say, well, if you only knew. It's a job. You go down to the studio. There are days you don't want to work, just like any other vocation. And it's work. The bottom line is: it's work. It's a lot of hustle. But what I found that feeds me is creating work that is coming from the inside, something that's stirring in me in terms of producing something that I feel like the world might be interested in, if that makes any sense. So it's risking, putting a part of myself out into the world. There are a lot of ups and downs.

I had a really painful summer this past summer. It was very, very slow. There was not much happening with commissions or things going on. But this too shall pass. There are these moments that we all have in our life that they won't last. I mean, we were in them for a spell, and then they will subside. Being an artist is a lot like that. It's like a roller coaster. I have highs, and I have lows. I have these ups and downs and successes, and then things slow down. But I've learned that wherever I am, it's going to change. It'll be different. It's like feelings. They pass, right? They're not forever.

Brandon: Yeah, I want to ask you about beauty again because we're talking about the beauty of work as the theme of the podcast. Are there a number of dimensions of beauty or dimensions of work where you might find beauty? One of them, you've talked a bit about process. I don't know if you would say there's any — would you say there's beauty in the process of work? Because there are days when certainly, as you say, you don't want to go to work. But are there experiences that you would consider beautiful in the process of making art?

Wayne: I would say, obviously, the right answer that you want to hear is yes. But I believe, I really believe that is true, that the process itself is life giving to me in terms of the collecting of pieces, or ephemera pieces of paper, or objects or things like this that have a story in and of themselves. I bring a lot of these pieces together to form a greater story. And so it feeds me. That making process, I come alive with the history of the objects or the subject that I'm bringing to life through these pieces and parts, which also I think speaks to my draw to the human face and to portraiture, which I have done a lot of portraits in my career.

The complexity of human beings in our face, everybody's drawn to the face of another being in relationship. Because that's how we communicate. It's by looking at each other. It's like John O'Donoghue. The poet, John O'Donoghue, says we engage each other, and we see each other. But we don't really know each other. We don't know the interior world of somebody. And so my portraiture consists of a lot of objects and complexities that when they're brought together, they form the visual of the person that I'm bringing to life. That's why I love mixed media art. It's because you can pull a little bit from each direction or collect objects and bring them together to tell a larger story. They each have their own little story in and of themselves. But you bring them together, and it's this giant puzzle that has a draw for people to be curious more about.

Brandon: Talk about the product. Talk about the work you produce and how you've developed — what you have is, I think, a really unique style. How did that come about, and how would you characterize your art? Perhaps maybe how do people describe Wayne Brezinka's art, and then to what extent do you agree with those descriptions?

Wayne: Well, I'll tell you this. It's very dimensional. There's a lot of depth to my work in-person. It's very difficult to communicate that on digital platforms, on the computer, online, on my website. Often, people will see it. They'll be attracted to it. They'll like it. Then they'll come to a show and say, oh, my gosh. I had no idea your work was 3D. And I'd go, well, how could that be? Because I'm trying my best to communicate that it's got shadow and depth.

You mentioned the word signature, which my associate, Laura, actually wrote that in the bio. I'm looking at a piece over here. That's why I keep looking off the side. There's a portrait of Willie Nelson. I was commissioned by the Washington Post to do Willie Nelson's obituary portrait. He's not passed away yet, so it's not public. But that's what I'm looking at in the corner. There's a lot of pieces and parts. It has grown over the years. My style has taken on its own life in terms of I put pieces of foam board under a cardboard or pieces of paper to raise it up more. I just found it very interesting as I was working several years ago with the shadow and the depth. It just rose. It began rising off the canvas more. It wasn't planned. It wasn't thought through. It just kind of morphed into this style.

And I teach. When I lead workshops, I teach my students about it. I have a friend who's a CEO of a restaurant here in Nashville, very successful at what he does. I was afraid to begin teaching several years ago and share my secrets, if you will, on how I make my work. He said, Wayne, we have to remember that people aren't going to steal from you. They're not going to be able to do what you do. And the more you share, the more your circle widens. So the more you're like this and you're fearful about sharing how you do what you do or, in your case, expanding on beauty and the topic of beauty, the more you open up, the greater your circle becomes. And so I've shared very freely about how I create and the techniques I use for the hair on people or the depth of using foam board and things like that. But yeah, it's just kind of taken on its own life.

Brandon: So it has to be seen in-person to really get a sense of the depth and the dimensionality of what you're creating.

Wayne: Yeah. I mean, if I can hold this piece up to the camera. Let me grab one real quick. I think you can — can you see the depth of the foam board underneath here?

Brandon: Yeah.

Wayne: But when the light hits it a certain way, you can see the shadow.

Brandon: Exactly.

Wayne: And it almost becomes — it actually goes — that's the right way, I guess. Is it? Like this.

Brandon: Right.

Wayne: But yeah. So there's pieces of paper, music sheets and cloth and old written notes from people, which I love anything vintage, any handwritten journal entries or things like that. And it's on a wooden panel that's two inches thick. But that's what I mean. The depth and the shadow and the complexity of the image, it takes on a life of its own.

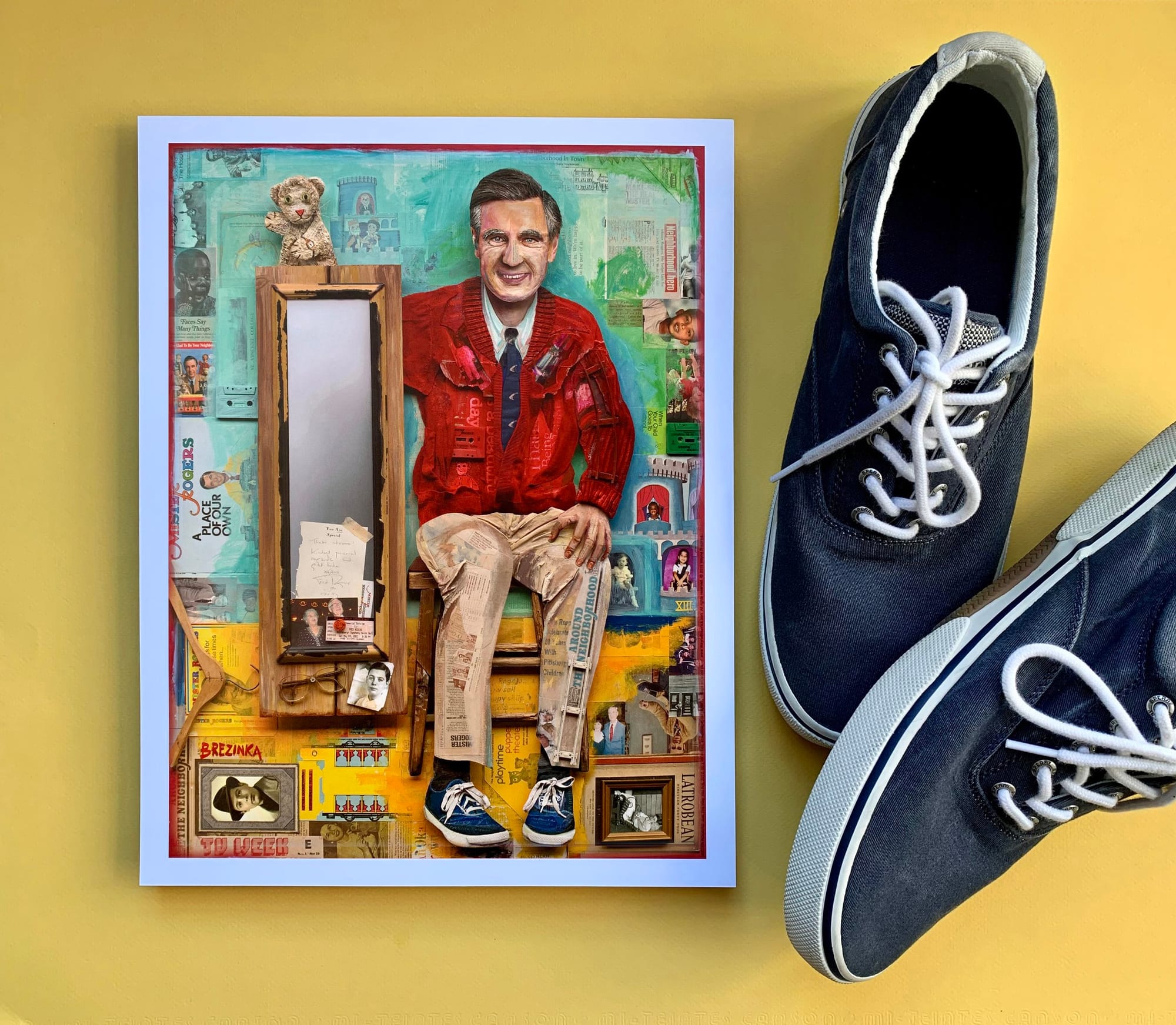

Brandon: You've done portraits of some very famous people. I think, is it typically like obituaries? I recall Mister Rogers. That was one that was recent. Could you tell something about how that come about, how do you get a commission to do those pieces, what the response has been from families of people who you've captured in your work?

Wayne: Yeah, I've done a few portraits for The Washington Post, several presidents for them. I learned early on in my career, when you think about a publication like the Washington Post or a magazine, the digital image that gets printed is not very large. It's a small image. But I learned early on that if I am commissioned to make these works, why not make them larger, like museum size, in hopes that they might be picked up by a museum or some public place that might want to acquire them? And so I started to build them much larger.

The Washington Post commission of President Obama was for the first part of his book, like part one of A Promised Land. So it was in support. The image was printed on the cover of the outlook section and supportive of his book that came out a few years ago. Once that published, the museum, the Obama Foundation, contacted me. So there's interest. People see it. It's published, and they begin to have interest in the images.

The Mister Rogers piece that you referenced was self-inspired, actually. I was in the movie theater with my wife watching the documentary that came out several years ago, Won't You Be My Neighbor, in tears. Just like, oh my gosh. I get inspired by other people, other individuals. And sometimes that draws me to create and bring them to life in portrait form. George Floyd. The murder of George Floyd several years ago, I was so moved to tears. I just brought his portrait to life as well. But the Mister Rogers portrait, I contacted the company up in Pittsburgh. I didn't even know if there was a Mister Rogers company existing in 2021 or 2022, whenever I did that portrait. And so I got online and just Googled. Fred Rogers production company is obviously still around. And so that has began a conversation with the Mister Rogers' neighborhood. They were very open and said that, Wayne, you can't just create this without our permission. You need permission. They're very protective of his likeness. And so we began a dialogue back and forth. Then I have an attorney friend that drew up a contract. Both the attorneys started talking to each other. They gave me permission to bring that to life with the understanding that I would find a place to exhibit it. Well, it ended up in five different locations around the country, and it took on its own life.

But it was very fun to do. Mrs. Rogers got involved. She called me at my studio as I was finishing it up one day. I had no idea who. It was a call from Pittsburgh. She goes, Wayne, this is Mrs. Rogers. I said, what? She said, I can't wait to see your portrait of Fred. We chatted for a few minutes. It was a lovely conversation. She said at the onset, I'm going through Fred's things, and I found a few of his bow ties. Would you like me to send them to you? And I said yes. I said that would be beautiful. We finished our conversation. Right before we hung up, I asked her a question. I said, Mrs. Rogers, I would love to honor you in this work. Is there anything in particular that you can think of whether it's an object or something that you might consider offering of your own? She paused for a minute and she said, well, there is one thing. I said, well, what's that? She goes, it's a photograph of Fred and I taken shortly before he died. She said, it's my favorite photograph of us together. I'll send that to you. And so in the package, she put this picture. You can see it. I'll send you an image of it. But he's got and she has the brightest, most engaging smiles on their faces. They're standing next to each other. Then she traveled to Washington, DC. David Brooks hosted an unveiling of the portrait at their home. She was there. She came and saw it for the first time. Moments like that, Brandon, things just started opening up. The art is part of it. But it's the life of the people around it I think that's much more life giving, I think, than just looking at the art itself.

Brandon: Yeah, the way in which art, I can see, it connects you and opens you up to people. It's also part of the process, it seems. Talk about beauty. As much as it is an object of what you're trying to create, I mean, to what extent are you trying to create beauty? Or if not beauty, what is it that you're trying to do? Because I imagine in some works, beauty is not the object. That's not the goal. Could you talk about those differences, whenever you're trying to create something that you would consider beautiful and that's the goal, and whenever you try to create something else, what are you trying to pursue there?

Wayne: I think that in life, I've learned, in regards to your question, beauty is engaged. The impact of beauty for me, personally, I'll just say for me, bumping up against the darkness and the grief and sorrow of life. I think to engage, to truly really engage beauty, you have to be hold in tandem this darkness or this grief that we all have. And so for me, personally, that has helped myself as an artist open up more. I've always been afraid of beauty, to be honest. I mean, when I was a younger artist, the word beauty and art and me, it ties into my story of my own past, my own trauma. The word beauty, and male, and me being six foot three, and being an artist, there was always this push pole of like, this isn't something you should be doing. You grew up in the country. There was always this, like, it's not masculine. You need to be doing something. All this bullshit is on my head.

Over the years, I've engaged that on a deeper level through poetry, through journaling, through, being with my friends, dialogue and conversation. I've opened up. Almost like these poppies just opened up. My life has opened up in a way that I truly am appreciative and grateful for, in terms of your question. So I don't set out to necessarily always make something that's beautiful. But the intention of my work is to — I guess the opposite of that would be not just make pretty things. I want to make art that pulls people in and makes them think and opens them up in a way that perhaps they weren't.

The art itself is a tool to open somebody up and direct them back to their own life, ask them questions within themselves. Like, what is this thing to me? How do I feel about this? What does this have to do with me in my life? These are the questions I want people to ask themselves as they look at my work sometimes. Or, if it's a subject or a portrait of a particular person, what does he or she have to do with me? So I think the beauty is in that. The beauty is the question. The beauty is the curiosity. The beauty is the unknown and the mystery. Those are other words and ways of being that I've grown to love: it's mystery and imagination, and just the unknown. As humans, we want to solve. We want answers. We want to know the why. And I think the beauty in life is the unknown, and the mystery, and the openness. That's in the art, too.

Brandon: Do you have examples of your work where you found that response to be quite easily forthcoming, where people tell you that this really has opened them up or has led them to raising questions for them? Are there a couple of pieces that come to mind for you where you're getting that response pretty immediately?

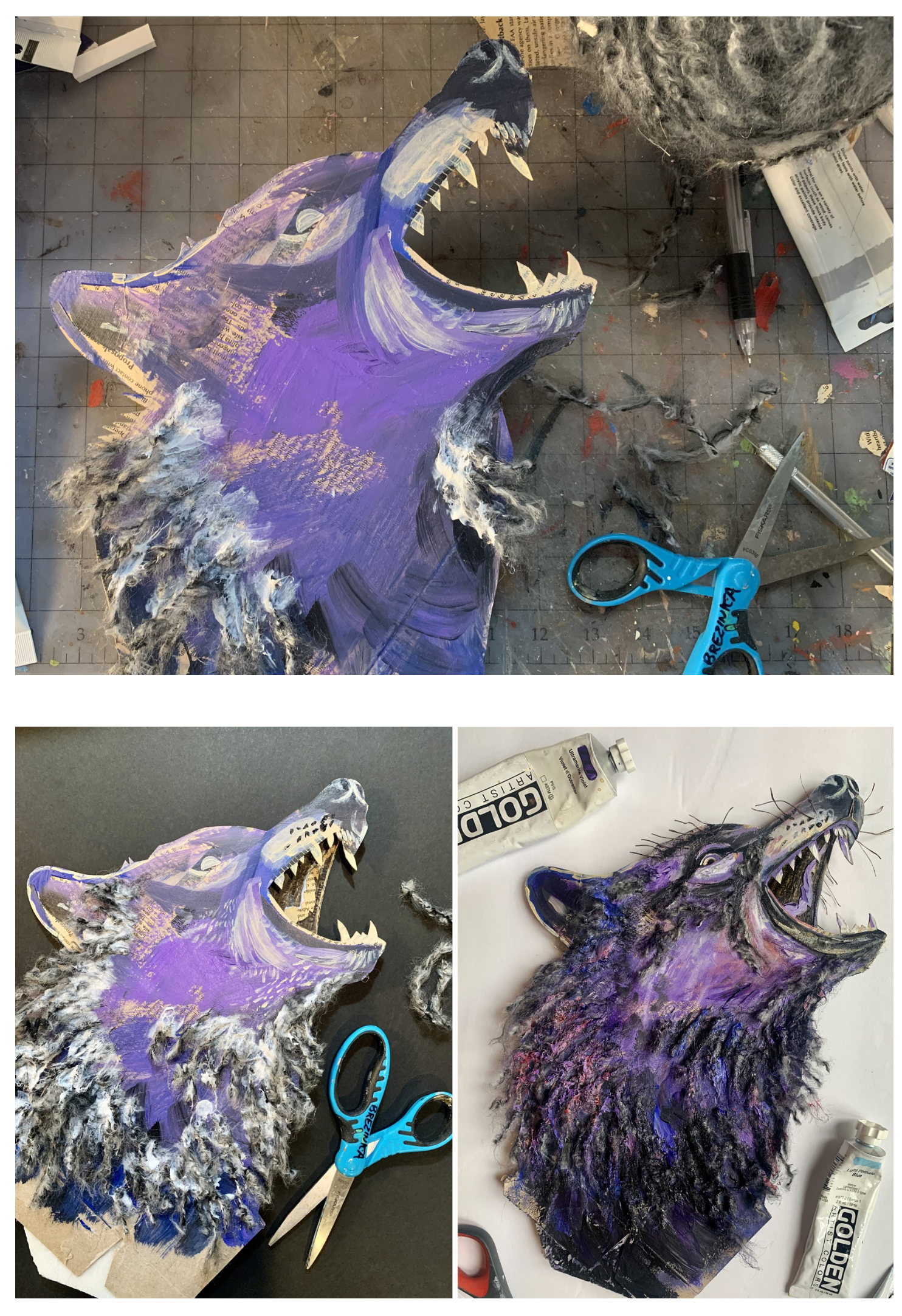

Wayne: Yes, there's a couple different — One, actually, was a piece that I created when you invited me to Washington earlier this year. I think I actually called the piece 'Flourish.' I had this dream prior to making this work. I wanted something personal to bring, to speak about. I was out in the universe. This is my dream. I was standing out in the universe completely unclothed. Not in a graphic sexual way but just out there, just with my arms up. Really not knowing. Just like feeling a very comfortable feeling. I'm trusting this bigger something. But underneath in the image, in the art, is this very angry wolf coming up at my feet. I'm actually standing on the snout of this wolf. And so, there's a lot of tension in that image. You've got this figure that's unclothed. It's very vulnerable. You also have this dark — it could be. It doesn't have to be dark. But you've got this ravaging wolf leaping at the heels of a human being. Again, what I mentioned earlier, I think in life, that's how many of us, if we're honest, that's who we are. I mean, there's this beauty, and this openness, and this trust, and this hope in something bigger. But there's always this darkness underneath, right? And so you can't have one without the other. There's both hands. So I wanted to illustrate that in the work, which I'll share that image with you after we finish.

There were questions about it at the events, and judgments. This is what it means for me. Ooh, that's a very evil looking image. I'm like, okay, that's great. People see what they want to see, right? That's part of the beauty of art, too. You can't force what I was hoping people to engage and witness on them. You have to let them bring their own narrative to it. And so, that's why I love making art, too. Because it doesn't solve. I love that phrase. We see what we want to see in life. And wherever we are at that time is what we're looking for. If you're looking for beauty, you're going to see it. If you're looking for the other shoe to drop, it's going to happen. So how do we exhale and just do the next thing on our list, if you will, and be okay with that? I mean, I'm rambling now.

Brandon: No, I see what you mean. It was a very striking piece, and I'm really glad that you brought that along. Because I think it was a great catalyst for a lot of reflection, a lot of discussion. I recall feeling that tension between yearning for the infinite and this sort of part of us that threatens to devour that. That was my kind of reaction to it. That we, on the one hand, are really drawn to infinity. On the other hand, there's sort of the wolf within that wants to devour everything. But yeah, you said there was another one that came to mind.

Wayne: There is. I don't know if you've seen it. It's on my website. I'll share it. It's my personal trauma art that I created years ago. It's just around my own story. I'll share the link with you. It's written about and the visuals are there. There's wolves in that one as well.

Brandon: Right. And that evoked a similar reaction from people?

Wayne: Oh, yeah, for sure. I mean, more so than the one that I just talked about. It's called Preyed Upon Prey. It's this image. It's very large. It's six feet, five feet by four feet, and 38 inches deep. It was a big installation piece that I was moved to bring to life but scared as hell to do.

I had a client that was doing a dream journal. She said, would you be interested in bringing one of your own dreams to life for this cover of our inaugural journal? I said, well, yeah, maybe. I might be. When she invited me, the first thought was this nightmare I had as a child. It come to mind that I should bring to life in art. I just pushed it down. I though no, I'm not going to do this. We continued our dialogue on email. And through some conversations with some friends of mine here in Nashville, musician friends and artistic friends, I said: I'm thinking about this, but I'm scared to bring it to life and let people see it. They said, you need to. I showed them the sketches. They said, you got to do this. And so, not only did I bring it to life, but I made it this huge, massive installation piece, not knowing really. I was kind of pissy about it. I thought, why am I doing this? It doesn't matter. It doesn't matter. Who cares? No one cares. It's going to go on the cover of this journal, and that'll be all fine.

It sat in my studio when I finished it and after I turned in the image for the journal. I had a workshop attendee sign up and come to make her deposit. Actually, ironically, she's coming to my studio today again this afternoon. But she came. Her name is Kathy. She came to my old studio with her deposit for the workshop. And just like many people that come in here, they get excited. They want to look around and go, oh, my gosh, this is where the magic happens, and blah, blah, blah. She saw that piece in the corner of my studio and she said, what is this? I go, well, that's my personal story. That's my trauma as a child. Her hands kind of just went like this, and she started to cry just looking at this piece. It was at that moment, Brandon, that I realized the power of art. This was maybe '15, 2014, 2013, however many years ago. But I thought, what is happening? She was literally in tears. She said, this is my story. She says, I've never told anybody that what you made is my story. She handed her deposit over to me, and she left the studio. She drove away. She texted me later. She said, I drove around for three hours after I left your studio crying in my car. She said, that is my story I've never told anybody, anybody, before. I was like, whoa.

There was another moment where a client came to my studio, a mother with her teenage daughter who was recording a record in Nashville. They came for a meeting to talk about the record packaging and the art for the packaging. They came in very excited to be in my studio and walked around. They saw that piece. The mother did. She said, what is this? I said, well, that's my personal story. There was a chair you can kind of see. I don't know if you see the chair. There's a chair. It's that chair over there.

Brandon: Yeah.

Wayne: She kind of fell into it. She said, that's my son's story. He was molested by his cub scout leader. I was like, what? So it just opened up and it, I think, gave people permission. It was a visual, a piece of art, that gave people permission to speak and to say for them what was true and for them what was probably decades of having not being able to have the words or the dialogue to speak, to push the word out. But anyway, that's the piece that I'm talking about that I'll share.

Brandon: That's really important, I think. Because what's at stake there is perhaps not beauty, right? There's something else going on. Maybe there is a sense of beauty and aptness in the way in which what you created expresses an experience that people can immediately connect with and resonate with. I don't know if beauty is the right word for that, but it seems like a really important function of art to do that. You've been doing some workshops around trauma. Is that right? Could you say a little bit about that?

Wayne: Yeah, actually, it's become one of my favorite things to do as a working artist. It's to facilitate and host and lead people back to themselves and help the light come back on in their eyes, as I like to say. I'm just using the tools, using the scissors, and the glue, and the painting, and the paper to a means to an end. There are different techniques that I use, I think. Obviously, you've been in one of my workshops. I let the art lead. I really am just the host or the facilitator. I've become, over the years, trained and aware enough of the room to understand what might be happening for somebody or what might be opening up and to just let it take over. But it's been really, really powerful — combat veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan, emergency hospital care workers, nurses, doctors, ER doctors, and the general public, people in different vocations. Art is a tool. It's not the only tool, but I think it's a really powerful medium to help an individual say something visually that maybe they don't have the words to speak out. So I absolutely love it. I'm hoping it will open up more opportunities for me to lead around the country.

Brandon: Could you say what people experienced there at this workshop? What is doing art, particularly using the techniques that you're leading them through, how does that help them process trauma? What is the goal there, or what have you seen happen?

Wayne: Yeah, in the context of veterans, combat veterans, many of them have struggled for years mentally with their mental health. Maybe some of them have TBI brain injuries. There's a number of factors happening for veterans in particular. Perhaps talk therapy hasn't worked, and other forms of therapy have not worked for them. But art and music are new, scientifically-proven methods to help an individual in ways that talk therapy or other forms of therapy can't.

And so I've been fortunate to be invited into these nonprofits and groups of individuals who lead veterans through using the arts as a way to heal. The only way that veterans will trust me is if I'm honest about my own story, if I'm vulnerable about my own trauma. I'm not a veteran myself. I've never been to war. The room changes. When I get honest, and I talk openly about my past, I can physically see the room change and the air lead out of their lungs. They feel safe in a way perhaps that they didn't before. They're kind of sizing me up. Like, what's this guy going to give us that we don't really know? But it's in that invitation and that gentle movement that I invite them to participate in certain exercises to get them out of their head and close their eyes. You can come back here. It's just incredible to watch what happens for them individuals. And afterwards, many of them have sent me — they've got three or four pieces around here. They'll send me pieces of art. I kind of get emotional thinking about it. But they're so grateful that somebody took the time to see them. They'll text me. They'll send me poems. And they're alive. Many of them are suicidal, had been before. That is what I love. It's like how I'm able to use the gift that I have of art and making art, not only solo in my studio and isolated down here but taking it out into groups and other people that can benefit them. That's what I love: to help another.

Brandon: What is happening to them in that process? Because I imagine a lot of people might be unfamiliar with the material or with the techniques or maybe even — I think as I remember the first time trying playing with glue, I feel, oh, no, I'm going to totally screw this up. It's going to be a big mess. How was that process of healing? What happens in the course of them giving themselves to that process?

Wayne: Well, I think I've learned it has to be set up in a way that is disarming. There are many people who have had bad experiences as children with their art teachers or making art as children. And so going in to a group of individuals, understanding that and actually giving them a place to voice that first changes the room. Also, mentioning to them that I'm not necessarily interested in what you make. I mean, I think it's important what you what the outcome of your art is. But it's not a piece that's going to be critiqued and judged on form and color and composition, and all of that in terms of the education aspect of art. But I'm more interested in what's happening for them as they're cutting, and as they're making, and as they're connecting to the image that they want to bring to life or the thought that they have wrestled with, that they don't have words to articulate but they want to bring it out in a visual form. So I'm there to help them as a guide bring this to life.

Often, those that are uneducated in art make the most incredible pieces of art that I have ever seen, as opposed to somebody who has an education and is academically-trained in the arts or in any form. There's an individual I've been reading a couple of years ago, Malidoma Somé. I don't know if you're familiar with his work. But he is from Africa. He does a lot of soul initiation work and was academically-trained in London, I think, in school, and would go back and visit his family in Africa. They kind of opposed the education aspect of things because it put walls around the soul. The soul is very free. It's like a wild animal. You can hope to see it, and you can hope to engage it and bump into it. But if you move too fast and too quick, you can scare it away. But anyway, I forget where I'm off on that. But art making and the not knowing is a gift in the context of a workshop because the outcome is just incredible.

Brandon: Wow. Fantastic. What is perhaps some advice you might have for people who are struggling with appreciating art or making art? Are there any tips you might have, any advice you might have for how people could could better engage with that?

Wayne: Just do it. I mean, we can talk ourselves out of so many different things, Brandon. You just have to put one foot in front of the other and move into the fear. They say whatever you're afraid of, that's your work. So if you're afraid of making art, if you're afraid of speaking engagements, if you're afraid of going out and dating somebody, do it. Move into it, and push into it. It's not going to be perfect. It's not going to be right. It's not going to be bright. It's not the right word. It may not be how you hope it will be. But the fact is, you're doing it. You're actually stepping into this energy and experimenting with that desire and that passion.

There's a term in recovery that many people use. It's, act as if you step into this. Even though you don't know how to do it, but you act as if. Then the acting as if it becomes a known way of being. And so I think that's true in art, too. It's like I'm not a trained visual mixed media artist. I've just discovered and learned on my own. In some ways, I think that is more attractive than being academically-trained in visual form. Not always. There is meaning in university training. Don't get me wrong. But I mean, the not knowing for me is proven to be beneficial in work, so I don't—

Brandon: Yeah, what's on the horizon for you? I mean, where are you seeing yourself in the next few years? Are there things that you're really drawn to? Maybe what would be a beautiful way to live out your vocation as an artist in the next few years?

Wayne: More workshop experiences. I think if I could find avenues and ways to plug in to different communities and different areas of teaching and facilitating, I mean, that is what feeds me, really, what feeds me and what keeps me going as a solo, isolated, working artist. I love music. I always crank up music down here. I'm listening to music and podcasts. Speaking of podcast, I don't know. You're a big podcast guy. But my latest greatest discovery is a guy named Craig Ferguson. He's a comedian. I don't know if you know Craig Ferguson.

Brandon: Oh, yeah, sure. He's got a good late-night show.

Wayne: He has a podcast called Joy. Are you familiar with it?

Brandon: No.

Wayne: It's fairly new. He's got seven episodes on it. It's really just him sitting down with his friends talking about what brings them joy, what in their life keeps them going. It's some of the most honest conversation, just sitting around. One of his friends is a chef. The chef friend makes a meal, and they talk over this meal in an hour-and-a-half conversation. I listen to podcasts and music. But being in the context of groups of people, I'm a very social person. I love other humans. That's what I hope happens.

Brandon: Well, I really enjoyed your workshops. We had this retreat two months ago maybe. It was really a powerful experience, I think, for all of us to go through that workshop. In spite of my, I'm constantly feeling awkward around glue, and scissors, and cloth, and collages, but the point wasn't to make a masterpiece, right? It was, I think, I really appreciated the way in which we ended up developing these collaborative pieces and then discussing and interpreting them. I think that was really quite an insightful experience for everybody. You really are, I think, I would say, masterful at facilitating that kind of process. I suppose you never know what you're going to get in a group of strangers coming together.

Wayne: It's a beautiful ending, though, isn't it? By collaborating on these pieces and then in the rotating exercise, coming back to your home place where you started, to look at the pieces that other individuals have touched and put their take on, it's proven to be a very powerful exercise for me to witness but also for the people engaging. It pushes the discomfort button in many people, which is what I'm after. People don't like to leave the work that they started and give it over to somebody else. They have to give it to somebody else. But that's part of the exercise, and that's what I think makes it beautiful. It's this community aspect and respect. There was a lot of respect in the positioning of certain items in these art pieces. And perhaps, the not knowing of why an image or an object is placed where it is, but the respect for leaving it there because it worked. It came together for a purpose and a reason.

In the end, having the dialogue with the group about where the individual started with the art piece and what their vision was, and what other people brought to it, it all made sense. It all came together. It happens that way every time. It's a powerful experience.

Brandon: Yeah, fantastic. Great. Wayne, where can we direct our listeners and viewers so they can learn more about your work?

Wayne: You can go to my website. It's my first and last name, waynebrezinka.com. There are many different images, and pieces of work, and links to different videos and things like that, show information.

Brandon: Awesome. Wayne, I really enjoyed this. It's always a pleasure talking to you. Any final thoughts on this theme of beauty at work that you want to leave us with?

Wayne: Well, I'm delighted to be with you. I was very nervous. I've told you this before. I thought, gosh, what do I have to bring to the table? I really don't measure up to Brandon.

Brandon: That's not true.

Wayne: I was coming downstairs in my studio early this morning at 6:30 thinking about this interview kind of dreading it, like, oh, my god. I got this interview this morning. I had my coffee in my hand. Then the question that came up in me was, what is this resistance, Wayne? It's not Brandon. It's not his invitation. It's in yourself. What do you think you don't have to bring your offer to the world? Then I thought, yeah, I got stuff to offer. So here we are.

Brandon: Amazing. That's true, yeah. And you do. I'm very grateful that you did check it out and that you're here.

Wayne: Yeah.

Brandon: That's been a lot of fun. Thanks, Wayne.

Wayne: Thank you, Brandon.

Brandon: Yeah, I hope to see you soon.

Wayne: Good to be with you.

If you found this post valuable, please share it. Also please consider supporting this project as a paid subscriber to support the costs associated with this work. You'll receive early access to content and exclusive members-only posts.